THE GREEK INTERPRETER | ギリシャ語通訳 |

DURING my long and intimate acquaintance with Mr. Sherlock Holmes I had never heard him refer to his relations, and hardly ever to his own early life. This reticence upon his part had increased the somewhat inhuman effect which he produced upon me, until sometimes I found myself regarding him as an isolated phenomenon, a brain without a heart, as deficient in human sympathy as he was preeminent in intelligence. His aversion to women and his disinclination to form new friendships were both typical of his unemotional character, but not more so than his complete suppression of every reference to his own people. I had come to believe that he was an orphan with no relatives living; but one day, to my very great surprise, he began to talk to me about his brother. | 私とシャーロックホームズとの長く親しい付き合いの中で / 私は彼が親族の事に触れるのを聞いたことがなかった / そして彼の子供時代のこともほとんど聞かなかった◆この部分に対して無言なのが / 彼が私に対して与える非人間的な印象をいくぶん強調させてきた / 遂には私自身が彼のことをしばしばこのように見なしてきた / いわく、孤立した現象 / 感情の無い頭脳 / いわく、人間的共感に欠けている / いわく、彼は抜群の知性である◆彼の女性嫌いと新しい友人を作りたがらないことは / どちらも彼の非感情的性格の特徴的なものだ / しかし、これ以上ではない / 彼の親族に関する完全な沈黙ほどには◆私は信じるようになっていた / 彼は親族が皆亡くなった孤児なのだと / しかしある日 / 私が仰天したことに / 彼は自分の兄弟について話し出した |

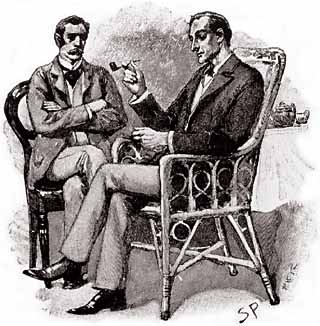

It was after tea on a summer evening, and the conversation, which had roamed in a desultory, spasmodic fashion from golf clubs to the causes of the change in the obliquity of the ecliptic, came round at last to the question of atavism and hereditary aptitudes. The point under discussion was, how far any singular gift in an individual was due to his ancestry and how far to his own early training. | ある夏の夕方のお茶の後のことだった / その時の会話は / 発作的な感じで取り留めなくあちこちに行き / ゴルフクラブから黄道傾斜角の変動まで / 遂には才能の遺伝や隔世遺伝の話に到った◆話のポイントと言うのは / どの程度個人の非凡な才能というのが / 家系によるものか / どの程度個人が訓練して獲得したものによるかだった |

“In your own case,” said I, “from all that you have told me, it seems obvious that your faculty of observation and your peculiar facility for deduction are due to your own systematic training.” | 「君自身の場合は」 / 私は言った / 「君が僕に話してくれたことを総合すると / 明らかなようだ / 君の観察の才能と独特の推理能力は / 君自身の系統的訓練の賜物だということは」 |

“To some extent,” he answered thoughtfully. “My ancestors were country squires, who appear to have led much the same life as is natural to their class. But, none the less, my turn that way is in my veins, and may have come with my grandmother, who was the sister of Vernet, the French artist. Art in the blood is liable to take the strangest forms.” | 「ある程度は」 / 彼は慎重に答えた◆「僕の祖先は田舎の郷士だった / 彼らはその身分としてごく普通の生活を送ったようだ◆しかし / それでも / 僕の血管を流れる才能は / もしかすると僕の祖母から来たものかもしれない / フランスの芸術家のベルネの妹だ◆芸術家の血というのは奇妙な形態をとりがちだから」 |

“But how do you know that it is hereditary?” | 「しかしなぜ遺伝性だと分かる?」 |

“Because my brother Mycroft possesses it in a larger degree than I do.” | 「僕の兄弟のマイクロフトが僕以上の能力を持っているからだ」 |

This was news to me indeed. If there were another man with such singular powers in England, how was it that neither police nor public had heard of him? I put the question, with a hint that it was my companion’s modesty which made him acknowledge his brother as his superior. Holmes laughed at my suggestion. | これは私には全くの初耳だった◆もしこんなに特異な才能を持った男がイギリスにもう一人いれば / 警察も市民もその男のことを聞いたことがないということがあるだろうか? / 私はこの質問をした / それは我が友人の謙遜だろうとほのめかして / 彼の兄弟が自分以上だという判断をしたのは◆ホームズは私の示唆を笑い飛ばした |

“My dear Watson,” said he, “I cannot agree with those who rank modesty among the virtues. To the logician all things should be seen exactly as they are, and to underestimate one’s self is as much a departure from truth as to exaggerate one’s own powers. When I say, therefore, that Mycroft has better powers of observation than I, you may take it that I am speaking the exact and literal truth.” | 「ワトソン」 / 彼は言った / 「僕は謙遜が美徳だという人間には賛成できない◆論理的な人間にとって / あらゆる出来事は正確にその通りに見なければいけない / そして自分を過小評価することは / 自分の能力を過大に見るのと同じだけ事実に反している◆だから僕が言う時 / マイクロフトは僕よりも観察力があると / 君はそれを正確に言っているととらえてかまわない / そして、文字通りの真実だと」 |

“Is he your junior?” | 「弟なのか?」 |

“Seven years my senior.” | 「七歳上の兄だ」 |

“How comes it that he is unknown?” | 「なぜ彼は世に知られていないのだ?」 |

“Oh, he is very well known in his own circle.” | 「彼は自分の仲間内ではよく知られているよ」 |

“Where, then?” | 「どこの事なんだ?」 |

“Well, in the Diogenes Club, for example.” | 「まあ、例えばディオゲネスクラブとか」 |

I had never heard of the institution, and my face must have proclaimed as much, for Sherlock Holmes pulled out his watch. | そんな団体は聞いたことがなかった / そして私の表情がそれを表していたに違いない / ホームズは時計を引っ張り出した |

| |

“The Diogenes Club is the queerest club in London, and Mycroft one of the queerest men. He’s always there from quarter to five to twenty to eight. It’s six now, so if you care for a stroll this beautiful evening I shall be very happy to introduce you to two curiosities.” | 「ディオゲネスクラブはロンドンで最も変わったクラブだ / そしてマイクロフトは最も変わった男の一人だ◆彼はいつも四時四十五分から七時四十分までそこにいる◆いま六時だ / だからもし君がこの気持ちよい夕べをちょっと歩く気があるなら / 僕は喜んで君にその変わった二つを紹介しよう」 |

Five minutes later we were in the street, walking towards Regent’s Circus. | 五分後我々は通りに出て / リージェント・サーカスの方に歩き出した |

“You wonder,” said my companion, “why it is that Mycroft does not use his powers for detective work. He is incapable of it.” | 「君は不思議に思っているだろう」 / ホームズは言った / 「なぜマイクロフトが彼の能力を捜査に使わないのかと◆彼にはその能力がないのだ」 |

“But I thought you said– –” | 「しかし、君は言ったじゃないか…」 |

“I said that he was my superior in observation and deduction. If the art of the detective began and ended in reasoning from an armchair, my brother would be the greatest criminal agent that ever lived. But he has no ambition and no energy. He will not even go out of his way to verify his own solutions, and would rather be considered wrong than take the trouble to prove himself right. Again and again I have taken a problem to him, and have received an explanation which has afterwards proved to be the correct one. And yet he was absolutely incapable of working out the practical points which must be gone into before a case could be laid before a judge or jury.” | 「僕は、観察力と推理力で彼が僕の上を行くと言った◆もし探偵業の技術が / 安楽椅子の上の推理で終始するなら / 兄は世界最高の犯罪捜査官だろう◆しかし彼には野心も活力もない◆彼は自分の結論を確かめるために外出さえしない / 間違っていると思われてもいい / 自分自身で正しいと証明する手間をかけるくらいなら◆何度も僕は彼のところに問題を持っていった / そして解釈を受け取った / 後になって正しいと証明される◆それでも / しかし彼は完全にやり遂げる事が出来ない / 実務的な点を / 裁判官か陪審員の前に提出するためにやっておかなければならない」 |

“It is not his profession, then?” | 「では、彼は職業にしていないのか?」 |

“By no means. What is to me a means of livelihood is to him the merest hobby of a dilettante. He has an extraordinary faculty for figures, and audits the books in some of the government departments. Mycroft lodges in Pall Mall, and he walks round the corner into Whitehall every morning and back every evening. From year’s end to year’s end he takes no other exercise, and is seen nowhere else, except only in the Diogenes Club, which is just opposite his rooms.” | 「全く違う◆僕が生活の糧にしている事は / 彼にとっては好事家のただの趣味だ◆彼は数字には物凄い才能があるので / いくつかの政府機関で会計監査をやっている◆マイクロフトはペル・メルに住み / 毎朝角を曲がったホワイトホール通りまで歩いて行き / 毎晩戻ってくる◆一年中他の運動は全くしない / そして他の場所には行かない / ディオゲネスクラブ以外には / そこは彼の家のちょうど向かいだ」 |

“I cannot recall the name.” | 「その名前は聞いたことがないが」 |

“Very likely not. There are many men in London, you know, who, some from shyness, some from misanthropy, have no wish for the company of their fellows. Yet they are not averse to comfortable chairs and the latest periodicals. It is for the convenience of these that the Diogenes Club was started, and it now contains the most unsociable and unclubable men in town. No member is permitted to take the least notice of any other one. Save in the Stranger’s Room, no talking is, under any circumstances, allowed, and three offences, if brought to the notice of the committee, render the talker liable to expulsion. My brother was one of the founders, and I have myself found it a very soothing atmosphere.” | 「まず無いだろう◆ロンドンには沢山の男がいる / いいか / 彼らは / ある者は恥ずかしさから / ある者は人嫌いから / 友人を作りたいとは思わない◆しかし彼らも座り心地のよい椅子や定期刊行物の最新号を避けている訳ではない◆彼らの利便のためだ / ディオゲネスクラブが始まったのは / 今ではこの街で最も非社交的な人間が加入している◆他のメンバーの事をほんの僅かでも話題にすることは全員禁止されている◆訪問者の部屋を覗いて / しゃべる事は一切 / どんな状況下であっても / 許されない / そして三度の違反が / 委員会の知るところとなれば / 違反者には追放が言い渡される◆兄は創始者の一人だが / 僕自身も非常に落ち着く雰囲気のところだと思う」 |