| グロリア・スコット号事件 8 | グロリア・スコット号事件 9 |

“These are the very papers, Watson, which he handed to me, and I will read them to you, as I read them in the old study that night to him. They are endorsed outside, as you see, ‘Some particulars of the voyage of the bark Gloria Scott, from her leaving Falmouth on the 8th October, 1855, to her destruction in N. Lat. 15° 20', W. Long. 25° 14', on Nov. 6th.’ It is in the form of a letter, and runs in this way. | 「これがその文書だ / ワトソン / 彼が僕に手渡した / 僕が君に読もうとしている / あの夜彼に古い書斎で読んだように◆これは外にサインがしてある / 見ての通り / 『バーク船グロリア・スコット号の航海のある顛末 / 1855年10月8日にファルマスを出航し / 11月6日、北緯15度20分、西経25度14分に破壊されるまで』 / これは手紙の形式になっていて / このように書かれている」 |

“ ‘My dear, dear son, now that approaching disgrace begins to darken the closing years of my life, I can write with all truth and honesty that it is not the terror of the law, it is not the loss of my position in the county, nor is it my fall in the eyes of all who have known me, which cuts me to the heart; but it is the thought that you should come to blush for me – you who love me and who have seldom, I hope, had reason to do other than respect me. But if the blow falls which is forever hanging over me, then I should wish you to read this, that you may know straight from me how far I have been to blame. On the other hand, if all should go well (which may kind God Almighty grant!), then, if by any chance this paper should be still undestroyed and should fall into your hands, I conjure you, by all you hold sacred, by the memory of your dear mother, and by the love which has been between us, to hurl it into the fire and to never give one thought to it again. | 「『愛する息子へ / 今近づきつつある不名誉は / 私の人生の終わりの年を陰鬱なものにし始めている / 私は全てを正直に書くことが出来る / 法が恐ろしい事ではない / この地域での立場を失う事ではない / 知人の目から見て落ちぶれて見える事ではない / 私の心がさいなまれるのは / それは、この考えのためだ / お前が私のために恥ずかしい思いをするという / / 私を愛してくれるお前 / 私を、そう願うが、 / 尊敬以外の気持ちでほとんど見ない◆しかしもしずっと私の頭上にある一撃が下されたなら / その時私はこれをお前に読んで欲しい / お前は直接私から知ることが出来るから / どれくらい私が責めを負わねばならないか◆一方で / もし全てが上手く行けば(慈愛ある全能の神がそうして下るように!) / その時 / もしひょっとしてこの書類が / 破棄されずにお前の手に渡れば / 私はお前に懇願する / お前の持っている全ての神聖さに掛けて / お前の愛する母の記憶に掛けて / 私とお前の間の愛情に掛けて / これを火の中にくべてくれ / 誰も決してこれを思い出すことがないように』」 |

“ ‘If then your eye goes on to read this line, I know that I shall already have been exposed and dragged from my home, or, as is more likely, for you know that my heart is weak, be lying with my tongue sealed forever in death. In either case the time for suppression is past, and every word which I tell you is the naked truth, and this I swear as I hope for mercy. | 「『もし、お前がこの行を読んでいるなら / 私には分かっている / 私の秘密が暴露され家から引きずり出されているか / または / もっとありそうなのは / 知っての通り私は心臓が弱いので / 死によって私の口は永遠に閉ざされているか◆どちらにしても隠しておかねばならない時は過ぎ / 私がお前に言う言葉は全てあからさまな真実だ / 慈悲を願う神にかけてこれを誓う』」 |

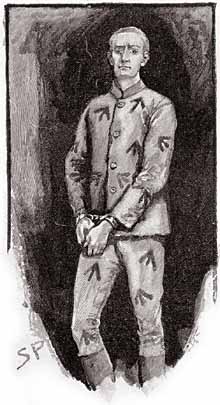

“ ‘My name, dear lad, is not Trevor. I was James Armitage in my younger days, and you can understand now the shock that it was to me a few weeks ago when your college friend addressed me in words which seemed to imply that he had surprised my secret. As Armitage it was that I entered a London banking-house, and as Armitage I was convicted of breaking my country’s laws, and was sentenced to transportation. Do not think very harshly of me, laddie. It was a debt of honour, so called, which I had to pay, and I used money which was not my own to do it, in the certainty that I could replace it before there could be any possibility of its being missed. But the most dreadful ill-luck pursued me. The money which I had reckoned upon never came to hand, and a premature examination of accounts exposed my deficit. The case might have been dealt leniently with, but the laws were more harshly administered thirty years ago than now, and on my twenty-third birthday I found myself chained as a felon with thirty-seven other convicts in the ’tween-decks of the bark Gloria Scott, bound for Australia. | 「『私の名前は / 息子よ / トレバーではない◆私は若い頃、ジェームズ・アーミテージという名前だった / そして今は分かってもらえるだろう / 私がどんなにショックを受けたか / 数週間前 / お前の大学の友人が私に言った時 / 彼が私の秘密に驚いたとほのめかしているように見える言葉を◆アーミテージという名で私はロンドンの銀行に入り / そしてアーミテージという名で私はこの国の法律を侵害した / そして国外に追放となった◆私を厳しく判定しないでおくれ、息子よ◆それは信用借りと呼ばれるものだった / 私が払わなければならなかったのは / そして私は自分のものでない金に手をつけた / 私が穴埋めできるという確信のもとに / それが無くなっていると見つかるあらゆる可能性以前に◆しかし、非常に恐ろしい不運が続いて私を襲った◆私が見込んだ金は全く手に入れることができなかった / そして予定より早い勘定調査によって私の欠損金が見つかり◆この事件はもっと寛大に扱われたかもしれないが / しかし三十年前は今よりも厳しく法律が適用された / そして私の23歳の誕生日に / 私は重罪人として鎖に繋がれていた / 他の37人の受刑者と共に / オーストラリアに向かうバーク船、グロリア・スコット号の中甲板の中で』」 |

“ ‘It was the year ’55, when the Crimean War was at its height, and the old convict ships had been largely used as transports in the Black Sea. The government was compelled, therefore, to use smaller and less suitable vessels for sending out their prisoners. The Gloria Scott had been in the Chinese tea-trade, but she was an old-fashioned, heavy-bowed, broad-beamed craft, and the new clippers had cut her out. She was a five-hundred-ton boat; and besides her thirty-eight jail-birds, she carried twenty-six of a crew, eighteen soldiers, a captain, three mates, a doctor, a chaplain, and four warders. Nearly a hundred souls were in her, all told, when we set sail from Falmouth. | 「『1855年だった / クリミア戦争が一番激しかった時で / かつて囚人を搬送していた船は大部分黒海の輸送に使われていた◆そのため、政府はやむなく / 囚人を輸送するためにより小さく不適当な船を使わざるをえなかった◆グロリア・スコット号は中国との紅茶取引に使われた / しかし、この船は旧式の舳先の重い、船尾の大きな船で / 改装帆船に取って代われた◆この船は排水量五百トンで / 38人の囚人以外に / この船に乗っていたのは / 26人の船員 / 18人の兵士 / 船長一人 / 三人の助手 / 一人の医者 / 従軍牧師 / 四人の看守だった◆百人近い人間が乗り込んでいた / 全体で / 我々がファルマスから帆を上げた時』」 |

“ ‘The partitions between the cells of the convicts instead of being of thick oak, as is usual in convict-ships, were quite thin and frail. The man next to me, upon the aft side, was one whom I had particularly noticed when we were led down the quay. He was a young man with a clear, hairless face, a long, thin nose, and rather nut-cracker jaws. He carried his head very jauntily in the air, had a swaggering style of walking, and was, above all else, remarkable for his extraordinary height. I don’t think any of our heads would have come up to his shoulder, and I am sure that he could not have measured less than six and a half feet. It was strange among so many sad and weary faces to see one which was full of energy and resolution. The sight of it was to me like a fire in a snowstorm. I was glad, then, to find that he was my neighbour, and gladder still when, in the dead of the night, I heard a whisper close to my ear and found that he had managed to cut an opening in the board which separated us. | 「『囚人の独房の間の仕切りは / 分厚いオーク材の換わりに / 囚人船が普通そうであるような / 非常に薄く脆かった◆私の隣の男は / 船尾側の / 私が特に見覚えがあった男だった / 我々が波止場から引率されてきたとき◆彼は若い男で / 髭の無いさっぱりした顔をし / 長く薄い鼻で / ちょっとえらが張り◆頭をさっそうと空中に持ち上げ / 威張ったように歩いていた / そして / 何よりも / 非常に背が高いことが目に付いた◆囚人のだれの頭も / 彼の方の所まで届かなかった / 私は確実だと思った / 6フィート半は下らないと◆それは奇妙だった / 沢山の見るからに悲しく疲れきった顔の中で / 一人活力があって不屈なものは◆この光景は私には吹雪の中の炎のように見えた◆だから私は嬉しかった / 彼が私の隣の部屋になった事を知って / そしてさらに嬉しくなった / 真夜中に / 私は耳の近くでささやく声を聞き / 彼が我々の間にある板に何とかして穴を開けたのを見つけた時』」 |

“ ‘ “Hullo, chummy!” said he, “what’s your name, and what are you here for?” | 「『《やあ、同僚!》 / 彼は言った / 《名前はなんだ / そしてなぜここに来たんだ?》』」 |

“ ‘I answered him, and asked in turn who I was talking with. | 「『私は返答した / その代りに相手の名前を聞いた』」 |

“ ‘ “I’m Jack Prendergast,” said he, “and by God! you’ll learn to bless my name before you’ve done with me.” | 「『《俺は、ジャック・プレンダガストだ》 / 彼は言った / 《そしてきっと! / お前は俺の名前を拝み始めるだろう / 俺と付き合う前にな》』」 |

| |

“ ‘I remembered hearing of his case, for it was one which had made an immense sensation throughout the country some time before my own arrest. He was a man of good family and of great ability, but of incurably vicious habits, who had by an ingenious system of fraud obtained huge sums of money from the leading London merchants. | 「『私は彼の事件について覚えていた / 彼が起こしたものは / 国中に強烈なセンセーションを巻き起ていた / 私の逮捕のちょっと前に◆彼はいい家系で才能に恵まれていた / しかし直らない悪習があり / 彼は巧妙な詐欺の体系を持っていた / 名だたるロンドン商人から大金を獲得した』」 |

“ ‘ “Ha, ha! You remember my case!” said he proudly. | 「『《ハ、ハ! / 君は俺の事件を覚えているのか》 / 彼は自慢そうに言いました』」 |

“ ‘ “Very well, indeed.” | 「『《本当によく覚えているよ》』」 |

“ ‘ “Then maybe you remember something queer about it?” | 「『《なら、あの事件に関してちょっと奇妙なことがあるのを覚えているだろう?》』」 |

“ ‘ “What was that, then?” | 「『《それは何だ?》』」 |

“ ‘ “I’d had nearly a quarter of a million, hadn’t I?” | 「『《俺は約25万ポンドを持っていたはずだな?》』」 |

“ ‘ “So it was said.” | 「『《そう言われているな》』」 |

“ ‘ “But none was recovered, eh?” | 「『《しかし、全く取り返せなかった?》』」 |

“ ‘ “No.” | 「『《その通りだ》』」 |

“ ‘ “Well, where d’ye suppose the balance is?” he asked. | 「『《なら、その差はどうなったと思う?》 / 彼は尋ねた』」 |

“ ‘ “I have no idea,” said I. | 「『《分からんな》 / 私は言った』」 |

“ ‘ “Right between my finger and thumb,” he cried. “By God! I’ve got more pounds to my name than you’ve hairs on your head. And if you’ve money, my son, and know how to handle it and spread it, you can do anything. Now, you don’t think it likely that a man who could do anything is going to wear his breeches out sitting in the stinking hold of a rat-gutted, beetle-ridden, mouldy old coffin of a Chin China coaster. No, sir, such a man will look after himself and will look after his chums. You may lay to that! You hold on to him, and you may kiss the Book that he’ll haul you through.” | 「『《俺がこの手に握っているのさ》 / 彼は叫んだ◆《神に誓ってな! / 俺はお前の髪の毛よりも多いポンドを自分の物にしている◆そしてもしその金をもっていて / どうやって扱ってばら撒くか知っていれば / 何でも出来る◆考えられないだろう / 何でもできる力をもった男が / こういう運命にあると / ズボンを擦り切らして / 臭い船倉に座っている / ネズミにかじられ / キクイムシに喰われた / かび臭い古いボロ船 / 中国貿易船の◆いや / こういう男は自分の面倒も仲間の面倒も見ることになる◆これに付いて行った方がいいぜ / こいつにしがみついて / そして聖書にキスして / そいつがお前を引き揚げてくれるように祈りな》』」 |

“ ‘That was his style of talk, and at first I thought it meant nothing; but after a while, when he had tested me and sworn me in with all possible solemnity, he let me understand that there really was a plot to gain command of the vessel. A dozen of the prisoners had hatched it before they came aboard, Prendergast was the leader, and his money was the motive power. | 「『彼はこういう話し方をし / 最初は私はなんとも思っていなかったが / しかし、しばらくして / 彼が私をテストし、誓わせた時 / これ以上ないほど厳粛に / 彼は私に分からせた / 船の指揮を乗っ取る計画が実際にあると◆十二名の囚人がその計画に加担していた / 船に乗り込む前に / プレンダガストが首謀者だった / そして彼の金がその動機だった』」 |

“ ‘ “I’d a partner,” said he, “a rare good man, as true as a stock to a barrel. He’s got the dibbs, he has, and where do you think he is at this moment? Why, he’s the chaplain of this ship – the chaplain, no less! He came aboard with a black coat, and his papers right, and money enough in his box to buy the thing right up from keel to main-truck. The crew are his, body and soul. He could buy ’em at so much a gross with a cash discount, and he did it before ever they signed on. He’s got two of the warders and Mereer, the second mate, and he’d get the captain himself, if he thought him worth it.” | 「『《俺は相棒が一人いる》 / 彼は言った / 《なかなかめぐり合えない、いい奴だ / 台尻と銃身のようにぴったりだ◆奴が金を預かっている / 今現在どこに奴がいると思う? / なんと / 奴はこの船の教戒師だ / / なんと教戒師だ / 奴は乗り込んでいる / 黒服を着て / ちゃんとした書類を持って / 金が一杯詰まった箱を持って / 竜骨からマストの天辺まで買い占める◆乗組員は完全に奴の思い通りだ◆現金割引をしても相当な金で彼らを買収した / 奴は彼らがこの船に乗る契約をする前にそうしていた◆彼は監視人と二等航海士メーラーの二人を / 船長自身も仲間に引き入れるだろう / もしそれに値すると思えば》』」 |

“ ‘ “What are we to do, then?” I asked. | 「『《それじゃ、我々の役目は何だ?》 / 私は尋ねた』」 |

“ ‘ “What do you think?” said he. “We’ll make the coats of some of these soldiers redder than ever the tailor did.” | 「『《どう思う?》 / 彼は言った◆《兵士の何人かの上着を / どんな仕立て屋よりも赤く染めてやろうとしているのさ》』」 |

“ ‘ “But they are armed,” said I. | 「『《しかし、銃を持っているぞ》 / 私は言った』」 |

“ ‘ “And so shall we be, my boy. There’s a brace of pistols for every mother’s son of us; and if we can’t carry this ship, with the crew at our back, it’s time we were all sent to a young misses’ boarding-school. You speak to your mate upon the left to-night, and see if he is to be trusted.” | 「『《こっちもだ◆一人当たり拳銃が二丁 / もし我々がこの船を占領できなかったら / 船員がついていて / みんなで寄宿舎女学校に行った方がいいな◆今夜左側の囚人に話をして / 彼が信用できる奴か見極めてくれ》』」 |

| グロリア・スコット号事件 8 | グロリア・スコット号事件 9 |