| オレンジの種五つ 6 | オレンジの種五つ 7 |

“I think, Watson,” he remarked at last, “that of all our cases we have had none more fantastic than this.” | 「思うのだが / ワトソン」 / 彼は遂に口を開いた / 「我々が扱った全ての事件で / これよりも奇妙なものはない」 |

| |

“Save, perhaps, the Sign of Four.” | 「多分『四つの署名』を除いては」 |

“Well, yes. Save, perhaps, that. And yet this John Openshaw seems to me to be walking amid even greater perils than did the Sholtos.” | 「まあそうだ◆それ以外は◆しかしこのジョン・オープンショーは僕には / ショルト一家よりも一層大きな危険の中を歩いているように思える」 |

“But have you,” I asked, “formed any definite conception as to what these perils are?” | 「しかしすでに」 / 私は尋ねた / 「その危険がどんなものかはっきりした考えがあるのだろう?」 |

“There can be no question as to their nature,” he answered. | 「彼らの正体には疑問の余地はない」 / 彼は答えた |

“Then what are they? Who is this K. K. K., and why does he pursue this unhappy family?” | 「では何者だ? / K.K.K.とは誰のことだ / そしてなぜこの家族を追い求めるんだ?」 |

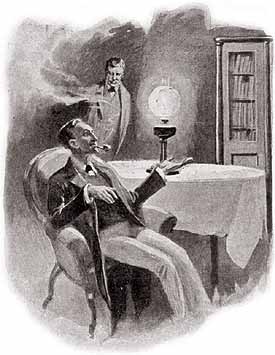

Sherlock Holmes closed his eyes and placed his elbows upon the arms of his chair, with his finger-tips together. “The ideal reasoner,” he remarked, “would, when he had once been shown a single fact in all its bearings, deduce from it not only all the chain of events which led up to it but also all the results which would follow from it. As Cuvier could correctly describe a whole animal by the contemplation of a single bone, so the observer who has thoroughly understood one link in a series of incidents should be able to accurately state all the other ones, both before and after. We have not yet grasped the results which the reason alone can attain to. Problems may be solved in the study which have baffled all those who have sought a solution by the aid of their senses. To carry the art, however, to its highest pitch, it is necessary that the reasoner should be able to utilize all the facts which have come to his knowledge; and this in itself implies, as you will readily see, a possession of all knowledge, which, even in these days of free education and encyclopaedias, is a somewhat rare accomplishment. It is not so impossible, however, that a man should possess all knowledge which is likely to be useful to him in his work, and this I have endeavoured in my case to do. If I remember rightly, you on one occasion, in the early days of our friendship, defined my limits in a very precise fashion.” | シャーロックホームズは目を閉じ / 椅子の肘掛に肘を置いた / 指先を押し当てて◆「理想的な論者は」 / 彼は言った / 「するだろう / 一度見せられた時 / あらゆる側面の中の一つの事実を / それから推理するだろう / そこに到る全ての出来事の連鎖だけでなく / そこから発生する全ての結果まで◆キュビエが動物の全体を正確に説明できたように / たった一つの骨を仔細に調べることによって / だから推理家は / 一連の出来事の一つのつながりを完全に理解したなら / 他の全てのものを正確に説明できるべきだ / 以前のものも以後のものも◆我々はまだ結果を把握してはいない / 思考力のみが到達できる◆書斎で解けるかもしれない / 困惑させていた / 感覚で解決を求めていた全ての人を◆しかしこの技術を運ぶには / 頂上まで / 必要なことだ / 論者は全ての事実を利用できるべきだ / 知るところとなった / このこと自体は暗示している / 君にもすぐに分かるように / あらゆる知識を所有することを / これは / この自由教育と百科事典の時代でも / なかなか達成することは困難だ◆しかしそれは全く不可能というわけでもない / 一人の男が全ての知識を持つというのとは / それは彼の仕事におそらく役立つだろう / そして僕も自分がそうあろうと努力している◆もし僕の記憶が正しければ / ある機会に君は / 我々が知り合って浅い時期に / 非常に正確な記述で僕の限界を定義したね」 |

“Yes,” I answered, laughing. “It was a singular document. Philosophy, astronomy, and politics were marked at zero, I remember. Botany variable, geology profound as regards the mud-stains from any region within fifty miles of town, chemistry eccentric, anatomy unsystematic, sensational literature and crime records unique, violin-player, boxer, swordsman, lawyer, and self-poisoner by cocaine and tobacco. Those, I think, were the main points of my analysis.” | 「そうだな」 / 私は答えた / 笑いながら◆「変わった文書だった◆哲学 / 天文学 / 政治 / は0点だった / 私は覚えているよ◆植物学はむらがある / 地質学は深い知識がある / 街の50マイル以内の全ての地域の泥汚れに関しては / 化学は素晴らしい / 解剖学は非体系的 / 犯罪の文献と犯罪記録は独特 / バイオリン奏者 / ボクサー / 剣術家 / 法律家 / コカインとタバコの中毒者◆これが / 思うに / 僕の分析の主な点だったか」 |

Holmes grinned at the last item. “Well,” he said, “I say now, as I said then, that a man should keep his little brain-attic stocked with all the furniture that he is likely to use, and the rest he can put away in the lumber-room of his library, where he can get it if he wants it. Now, for such a case as the one which has been submitted to us to-night, we need certainly to muster all our resources. Kindly hand me down the letter K of the American Encyclopaedia which stands upon the shelf beside you. Thank you. Now let us consider the situation and see what may be deduced from it. In the first place, we may start with a strong presumption that Colonel Openshaw had some very strong reason for leaving America. Men at his time of life do not change all their habits and exchange willingly the charming climate of Florida for the lonely life of an English provincial town. His extreme love of solitude in England suggests the idea that he was in fear of someone or something, so we may assume as a working hypothesis that it was fear of someone or something which drove him from America. As to what it was he feared, we can only deduce that by considering the formidable letters which were received by himself and his successors. Did you remark the postmarks of those letters?” | ホームズは最後の項目に対してにやりとした◆「たしかに」 / 彼は言った / 「今僕は言うよ / その時も言ったように / 人間は小さな頭脳の部屋を維持しなければならない / 自分が使うであろう家具を備え付けて / そしてそれ以外のものは彼の蔵書の部屋から追い出せばよい / いつか必要な時に取り出せる場所に◆さて / 今夜我々に提出されたこのような事件では / 我々は間違いなく全ての英知を結集させなければならない◆アメリカ百科事典のKの項目を渡してもらえないか / 君の側の本棚にある◆ありがとう◆今、状況を考えてみよう / そしてそこから何が推論できるかを考えよう◆まず最初に / 我々は強く仮定するところから始めてよいだろう / オープンショー大佐は何らかの重大な理由があってアメリカを離れることになったという◆彼ぐらいの年齢の男は変えたりしない / 生活習慣を全て変えて / わざわざフロリダの過ごしやすい気候から引越しする / イギリスの片田舎の町で孤独な生活をするために◆彼のイギリスでの極端な孤独への偏愛は / 彼が誰か、あるいは何かを恐れていたという考えを示唆する / したがって作業仮説としてこう仮定していいだろう / 誰か、あるいは何かに対する恐れから彼はアメリカを離れたと◆彼が何を恐れていたかだが / 我々は例の恐ろしい手紙から推察するしかない / 彼とその後継者が受け取った◆手紙の消印に気付いたか?」 |

| オレンジの種五つ 6 | オレンジの種五つ 7 |