| オレンジの種五つ 3 | オレンジの種五つ 4 |

“My name,” said he, “is John Openshaw, but my own affairs have, as far as I can understand, little to do with this awful business. It is a hereditary matter; so in order to give you an idea of the facts, I must go back to the commencement of the affair. | 「私の名は」 / 彼は言った / 「ジョン・オープンショーです / しかし私自身の出来事は / 私が理解できるかぎり / ほとんどこの恐ろしい事件には関与していない◆これは先祖から続く出来事です / ですのであなたに事実関係を理解していただくのに / 私は事の起こりまで遡らなければなりません」 |

“You must know that my grandfather had two sons – my uncle Elias and my father Joseph. My father had a small factory at Coventry, which he enlarged at the time of the invention of bicycling. He was a patentee of the Openshaw unbreakable tire, and his business met with such success that he was able to sell it and to retire upon a handsome competence. | 「まず知っていただきたいのは、私の祖父は二人の息子がいたことです / / 伯父のエリアスと父のジョーゼフです◆私の父はコベントリーに小さな工場を構えていました / それを彼は自転車が発明されたときに拡張しました◆父はオープンショーの無パンクタイアの特許所有者でした / そして彼の仕事は非常な成功を収め / 彼はそれを売ってかなりの資産を持って引退することができました」 |

“My uncle Elias emigrated to America when he was a young man and became a planter in Florida, where he was reported to have done very well. At the time of the war he fought in Jackson’s army, and afterwards under Hood, where he rose to be a colonel. When Lee laid down his arms my uncle returned to his plantation, where he remained for three or four years. About 1869 or 1870 he came back to Europe and took a small estate in Sussex, near Horsham. He had made a very considerable fortune in the States, and his reason for leaving them was his aversion to the negroes, and his dislike of the Republican policy in extending the franchise to them. He was a singular man, fierce and quick-tempered, very foul-mouthed when he was angry, and of a most retiring disposition. During all the years that he lived at Horsham, I doubt if ever he set foot in the town. He had a garden and two or three fields round his house, and there he would take his exercise, though very often for weeks on end he would never leave his room. He drank a great deal of brandy and smoked very heavily, but he would see no society and did not want any friends, not even his own brother. | 「伯父のエリアスはアメリカに移住しました / 彼が若いときに / そしてフロリダで農場主になりました / そこで非常に上手くやっていたと聞いています◆戦争の際 / 彼はジャクソン兵として戦い / その後はフッドの下で / そこで彼は連隊長に出世しました◆リー司令官が降伏したとき伯父は農場に戻りました / そこで3・4年いました◆1869年か1870年ころ彼はヨーロッパに戻り / ホーシャム近くのサセックスに小さな屋敷を構えました◆彼はアメリカで非常に大きな財産を蓄えました / 彼がアメリカを離れたのは / 黒人に対する反感と / 共和党の政策が気に入らなかった / 黒人に参政権を与えるという◆彼は変わった人間でした / 激しく、怒りっぽく / 怒った時の言葉は物凄く汚く / 引きこもりの性格が強かった◆ホーシャムに住んでいた年の間 / 私は彼が町に一歩でも足を踏み入れたか疑問に思っています◆彼の家の周りには一つの庭と2・3の農場がありました / そこで彼は運動していました / ですが何週間も続けて部屋から出ないことがよくありました◆彼はブランデーをがぶ飲みしタバコも非常に沢山吸いました / しかし彼は付き合いをまったくせず友人も欲しいとは思いませんでした / 兄弟さえもです」 |

“He didn’t mind me; in fact, he took a fancy to me, for at the time when he saw me first I was a youngster of twelve or so. This would be in the year 1878, after he had been eight or nine years in England. He begged my father to let me live with him, and he was very kind to me in his way. When he was sober he used to be fond of playing backgammon and draughts with me, and he would make me his representative both with the servants and with the tradespeople, so that by the time that I was sixteen I was quite master of the house. I kept all the keys and could go where I liked and do what I liked, so long as I did not disturb him in his privacy. There was one singular exception, however, for he had a single room, a lumber-room up among the attics, which was invariably locked, and which he would never permit either me or anyone else to enter. With a boy’s curiosity I have peeped through the keyhole, but I was never able to see more than such a collection of old trunks and bundles as would be expected in such a room. | 「彼は私のことは嫌いではなかったようです / というより / 私のことを気に入っていたようです / 彼と私が初めて会ったのは / 私が12歳くらいの子供の時でした◆これは1878年だったかもしれません / イギリスに来て8年か9年経ったころです◆彼は私の父に私と一緒に住ませて欲しいと頼み / 彼は私には非常に親切にしてくれました◆素面のときは / 私とバックギャモンやドラウトをして遊ぶのが楽しみでした / そして彼は私を代理人にしました / 使用人に対しても商人に対しても / それなので私が16歳になるまでには / 完全に家の長となっていました◆私は全ての鍵を持ち / どこでも好きなところに行け / 好きなことをしました / 私が彼のプライバシーを乱さない限り◆奇妙な例外が一つありました / しかし / 彼は一つの部屋を持っていました / 屋根裏にある一つの物置部屋 / そこは常に鍵が掛けられていて / そして私も他の誰にも入ることを許さなかった◆子供の好奇心で私は鍵穴から覗き込んだものですが / しかし私は見ることが出来ませんでした / トランクや包みの集積以上のものは / そういう部屋に置いておきそうな」 |

“One day – it was in March, 1883 – a letter with a foreign stamp lay upon the table in front of the colonel’s plate. It was not a common thing for him to receive letters, for his bills were all paid in ready money, and he had no friends of any sort. ‘From India!’ said he as he took it up, ‘Pondicherry postmark! What can this be?’ Opening it hurriedly, out there jumped five little dried orange pips, which pattered down upon his plate. I began to laugh at this, but the laugh was struck from my lips at the sight of his face. His lip had fallen, his eyes were protruding, his skin the colour of putty, and he glared at the envelope which he still held in his trembling hand, ‘K. K. K.!’ he shrieked, and then, ‘My God, my God, my sins have overtaken me!’ | 「ある日 / / 1883年3月でした / / 外国の切手を貼った手紙がテーブルの上に置いてありました / 伯父の皿の前です◆伯父にとって手紙を受け取るのはあまりないことでした / 支払はすべて現金払いで / 彼には友人はどんなところにもいませんでした◆『インドから!』 / 彼はそれを取り上げて言いました / 『ポンディチェリの消印! / 何だろう?』 / 手早くそれを開くとき / 小さな乾いたオレンジの種が5粒転がり出ました / それが彼の皿にパラパラと落ちました◆私はこれを見て笑い出しましたが / その笑いは凍りつきました / 彼の顔を見て◆彼の顎は落ち / 目は飛び出し / 肌はパテのように灰色になり / そして彼は封筒をにらんでいました / まだ震える手にもっていた / 『ケイ、ケイ、ケイ!』 / 彼は叫びました / そして、 / 『マイゴッド! / 罪の報いがやってきた!』」 |

“‘What is it, uncle?’ I cried. | 「『それは何です / おじさん?』 / 私は叫んだ」 |

“‘Death,’ said he, and rising from the table he retired to his room, leaving me palpitating with horror. I took up the envelope and saw scrawled in red ink upon the inner flap, just above the gum, the letter K three times repeated. There was nothing else save the five dried pips. What could be the reason of his overpowering terror? I left the breakfast-table, and as I ascended the stair I met him coming down with an old rusty key, which must have belonged to the attic, in one hand, and a small brass box, like a cashbox, in the other. | 「『死だ』 / 彼は言った / そして彼はテーブルから立ち上がって自分の部屋に下がりました / 恐怖に震える私を残して◆私は封筒を取り上げ / 折り返しの裏側に赤いインクの殴り書きを見ました / 糊のすぐ上に / Kの文字が3つ繰り返されて◆中には乾いた種が5つ以外にはなにもありませんでした◆何が伯父の圧倒的な恐怖の原因となりえたのか? / 朝食のテーブルを後にして / 階段を上がっているとき / 私は伯父が降りてくるところに出会った / 古い錆びた鍵を / それはあの屋根裏部屋のものに違いなかった / 片手に / そして手提げ金庫のような小さな真鍮の箱を / もう一方の手に」 |

“‘They may do what they like, but I’ll checkmate them still,’ said he with an oath. ‘Tell Mary that I shall want a fire in my room to-day, and send down to Fordham, the Horsham lawyer.’ | 「『やつらはやりたいことをすればいい / しかしそれを打ち負かしてやる』 / 彼は罵倒と共に言った◆『メアリーに今日はわしの部屋に火が要ると言え / それからホーシャムのフォーダム弁護士へ使いを出せ』」 |

“I did as he ordered, and when the lawyer arrived I was asked to step up to the room. The fire was burning brightly, and in the grate there was a mass of black, fluffy ashes, as of burned paper, while the brass box stood open and empty beside it. As I glanced at the box I noticed, with a start, that upon the lid was printed the treble K which I had read in the morning upon the envelope. | 「私は言われたとおりにしました / 弁護士が到着したとき / 私は部屋に来るように呼ばれました◆暖炉は明るく燃えていました / 火床の中では黒く柔らかい灰の塊がありました / 紙の束が燃えたような / 真鍮の箱は開けられ空になってそばに置いてあった◆その箱を見て私は気づきました / ハッと / 蓋の上に3つのKが書かれていたのを / 私がその日の朝封筒に書かれていたのを読んだのと同じ」 |

“‘I wish you, John,’ said my uncle, ‘to witness my will. I leave my estate, with all its advantages and all its disadvantages, to my brother, your father, whence it will, no doubt, descend to you. If you can enjoy it in peace, well and good! If you find you cannot, take my advice, my boy, and leave it to your deadliest enemy. I am sorry to give you such a two-edged thing, but I can’t say what turn things are going to take. Kindly sign the paper where Mr. Fordham shows you.’ | 「『お前に頼みたい / ジョン』 / 伯父はいいました / 『私の遺言の証言者となることを◆わしは自分の財産を / すべての利益と不利益とともに / 私の弟 / お前の父 / その後それは / 間違いなく / お前に相続される◆もし平穏にそれを享受できるなら / 素晴らしいことだ / もしそうでないなら / お前はわしの忠告にしたがってくれ / それをお前の最悪の敵に渡せ◆お前に善にも悪にもなるものを遺すのはすまないが / 事態がどのように転ぶのか分からないのだ◆どうかこの書類のフォーダムさんの示す場所にサインして欲しい』」 |

“I signed the paper as directed, and the lawyer took it away with him. The singular incident made, as you may think, the deepest impression upon me, and I pondered over it and turned it every way in my mind without being able to make anything of it. Yet I could not shake off the vague feeling of dread which it left behind, though the sensation grew less keen as the weeks passed, and nothing happened to disturb the usual routine of our lives. I could see a change in my uncle, however. He drank more than ever, and he was less inclined for any sort of society. Most of his time he would spend in his room, with the door locked upon the inside, but sometimes he would emerge in a sort of drunken frenzy and would burst out of the house and tear about the garden with a revolver in his hand, screaming out that he was afraid of no man, and that he was not to be cooped up, like a sheep in a pen, by man or devil. When these hot fits were over, however, he would rush tumultuously in at the door and lock and bar it behind him, like a man who can brazen it out no longer against the terror which lies at the roots of his soul. At such times I have seen his face, even on a cold day, glisten with moisture, as though it were new raised from a basin. | 「私は言われるままに書類にサインしました / 弁護士はそれを持ち帰りました◆この奇妙な出来事は / おわかりでしょうが / 私に非常に強い印象を与えました / そしてじっくりと考えてみました / 私の心の中で色々な角度から / しかし何も明らかにすることはできませんでした◆しかし私は振り払うことはできませんでした / 漠然とした恐ろしい気持ちが残るのを / しかし動揺した気持ちは時間が経つにつれて薄らいできました / そして私たちの日常生活を脅かす事は何もおきませんでした◆しかし、私の伯父の変化は見て取れました◆酒は以前より多量に飲み / あらゆる付き合いは一層減らそうとしました◆ほとんどの時間を部屋のなかで過ごすようになり / ドアの内側から鍵をかけて / しかし時々酒の力を借りた狂乱のようなものが現れ / 家の外に勢いよく飛び出し / 手に拳銃を持って庭を走り回り / わしは誰も怖くないと叫びながら / わしは閉じ込められたりしない / 檻の中の羊のように / 人間であろうが悪魔であろうが◆このような発作が過ぎると / しかしながら / 伯父は騒々しくドアに向かって駆け出し / そして内側から鍵をかけ閂をしました / それ以上大胆には振舞えない人間のように / 心の底に横たわる恐怖に対して◆そういうときに伯父の顔を見ると / 寒い日でも / 汗が光っていました / 洗面器から顔を上げた直後のように」 |

| |

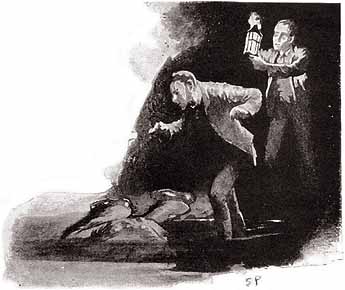

“Well, to come to an end of the matter, Mr. Holmes, and not to abuse your patience, there came a night when he made one of those drunken sallies from which he never came back. We found him, when we went to search for him, face downward in a little green-scummed pool, which lay at the foot of the garden. There was no sign of any violence, and the water was but two feet deep, so that the jury, having regard to his known eccentricity, brought in a verdict of ‘suicide.’ But I, who knew how he winced from the very thought of death, had much ado to persuade myself that he had gone out of his way to meet it. The matter passed, however, and my father entered into possession of the estate, and of some £14,000, which lay to his credit at the bank.” | 「この叔父の不安を終わらせるため / ホームズさん / そしてあなたの忍耐を酷使しないため / その夜がやってきました / 彼は酔って出かけて帰ってきませんでした◆彼は見つかりました / 私たちが探しに出かけて / アオコが浮いた小さな池に顔をうつぶせにした状態で / 庭の窪地にある◆暴行された跡はありませんでした / 水は2フィートの深さしかなく / だから陪審員は / 普段の伯父の奇行を考えて / 「自殺」の評決を下しました / しかし私は彼が死ぬと思って非常にひるんでいたことを知っていたので / 自分を納得させるのは大変でした / 伯父がわざわざそのようなことをしたと◆しかし、事件はそのように過ぎ / 私の父は財産を相続することになりました / 不動産と、銀行口座にあった約1万4千ポンドを」 |

“One moment,” Holmes interposed, “your statement is, I foresee, one of the most remarkable to which I have ever listened. Let me have the date of the reception by your uncle of the letter, and the date of his supposed suicide.” | 「ちょっとよろしいか」 / ホームズは割り込んだ / 「あなたのお話は / 私が見るところ / これまで聞いたなかで最も注目すべきものの一つだ◆日付を伺いたい / あなたの伯父が手紙を受け取った日と / 自殺とみなされる事件があった日を」 |

“The letter arrived on March 10, 1883. His death was seven weeks later, upon the night of May 2d.” | 「手紙は1883年3月10日に届きました◆伯父が死んだのは7週間後 / 5月2日の夜です」 |

“Thank you. Pray proceed.” | 「ありがとう、続きをどうぞ」 |

| オレンジの種五つ 3 | オレンジの種五つ 4 |