| Silver Blaze 9 | Silver Blaze 10 |

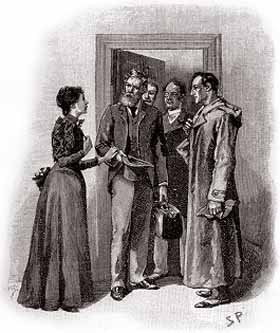

As we emerged from the sitting-room a woman, who had been waiting in the passage, took a step forward and laid her hand upon the inspector’s sleeve. Her face was haggard and thin and eager, stamped with the print of a recent horror.

“Have you got them? Have you found them?” she panted.

“No, Mrs. Straker. But Mr. Holmes here has come from London to help us, and we shall do all that is possible.”

“Surely I met you in Plymouth at a garden-party some little time ago, Mrs. Straker?” said Holmes.

“No, sir; you are mistaken.”

“Dear me! Why, I could have sworn to it. You wore a costume of dove-coloured silk with ostrich-feather trimming.”

“I never had such a dress, sir,” answered the lady.

“Ah, that quite settles it,” said Holmes. And with an apology he followed the inspector outside. A short walk across the moor took us to the hollow in which the body had been found. At the brink of it was the furze-bush upon which the coat had been hung.

“There was no wind that night, I understand,” said Holmes.

“None, but very heavy rain.”

“In that case the overcoat was not blown against the furze-bush, but placed there.”

“Yes, it was laid across the bush.”

“You fill me with interest. I perceive that the ground has been trampled up a good deal. No doubt many feet have been here since Monday night.”

“A piece of matting has been laid here at the side, and we have all stood upon that.”

“Excellent.”

“In this bag I have one of the boots which Straker wore, one of Fitzroy Simpson’s shoes, and a cast horseshoe of Silver Blaze.”

“My dear Inspector, you surpass yourself!” Holmes took the bag, and, descending into the hollow, he pushed the matting into a more central position. Then stretching himself upon his face and leaning his chin upon his hands, he made a careful study of the trampled mud in front of him. “Hullo!” said he suddenly. “What’s this?” It was a wax vesta, half burned, which was so coated with mud that it looked at first like a little chip of wood.

“I cannot think how I came to overlook it,” said the inspector with an expression of annoyance.

“It was invisible, buried in the mud. I only saw it because I was looking for it.”

“What! you expected to find it?”

“I thought it not unlikely.”

He took the boots from the bag and compared the impressions of each of them with marks upon the ground. Then he clambered up to the rim of the hollow and crawled about among the ferns and bushes.

“I am afraid that there are no more tracks,” said the inspector. “I have examined the ground very carefully for a hundred yards in each direction.”

“Indeed!” said Holmes, rising. “I should not have the impertinence to do it again after what you say. But I should like to take a little walk over the moor before it grows dark that I may know my ground to-morrow, and I think that I shall put this horseshoe into my pocket for luck.”

Colonel Ross, who had shown some signs of impatience at my companion’s quiet and systematic method of work, glanced at his watch. “I wish you would come back with me, Inspector,” said he. “There are several points on which I should like your advice, and especially as to whether we do not owe it to the public to remove our horse’s name from the entries for the cup.”

“Certainly not,” cried Holmes with decision. “I should let the name stand.”

The colonel bowed. “I am very glad to have had your opinion, sir,” said he. “You will find us at poor Straker’s house when you have finished your walk, and we can drive together into Tavistock.”

| Silver Blaze 9 | Silver Blaze 10 |