| The Dancing Men 5 | The Dancing Men 6 |

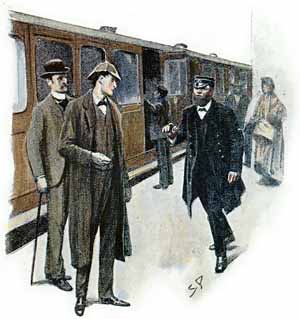

We had hardly alighted at North Walsham, and mentioned the name of our destination, when the stationmaster hurried towards us. “I suppose that you are the detectives from London?” said he.

A look of annoyance passed over Holmes’s face.

“What makes you think such a thing?”

“Because Inspector Martin from Norwich has just passed through. But maybe you are the surgeons. She’s not dead – or wasn’t by last accounts. You may be in time to save her yet – though it be for the gallows.”

Holmes’s brow was dark with anxiety.

“We are going to Riding Thorpe Manor,” said he, “but we have heard nothing of what has passed there.”

“It’s a terrible business,” said the stationmaster. “They are shot, both Mr. Hilton Cubitt and his wife. She shot him and then herself – so the servants say. He’s dead and her life is despaired of. Dear, dear, one of the oldest families in the county of Norfolk, and one of the most honoured.”

Without a word Holmes hurried to a carriage, and during the long seven miles’ drive he never opened his mouth. Seldom have I seen him so utterly despondent. He had been uneasy during all our journey from town, and I had observed that he had turned over the morning papers with anxious attention, but now this sudden realization of his worst fears left him in a blank melancholy. He leaned back in his seat, lost in gloomy speculation. Yet there was much around to interest us, for we were passing through as singular a countryside as any in England, where a few scattered cottages represented the population of to-day, while on every hand enormous square-towered churches bristled up from the flat green landscape and told of the glory and prosperity of old East Anglia. At last the violet rim of the German Ocean appeared over the green edge of the Norfolk coast, and the driver pointed with his whip to two old brick and timber gables which projected from a grove of trees. “That’s Riding Thorpe Manor,” said he.

As we drove up to the porticoed front door, I observed in front of it, beside the tennis lawn, the black tool-house and the pedestalled sundial with which we had such strange associations. A dapper little man, with a quick, alert manner and a waxed moustache, had just descended from a high dog-cart. He introduced himself as Inspector Martin, of the Norfolk Constabulary, and he was considerably astonished when he heard the name of my companion.

“Why, Mr. Holmes, the crime was only committed at three this morning. How could you hear of it in London and get to the spot as soon as I?”

“I anticipated it. I came in the hope of preventing it.”

“Then you must have important evidence, of which we are ignorant, for they were said to be a most united couple.”

“I have only the evidence of the dancing men,” said Holmes. “I will explain the matter to you later. Meanwhile, since it is too late to prevent this tragedy, I am very anxious that I should use the knowledge which I possess in order to insure that justice be done. Will you associate me in your investigation, or will you prefer that I should act independently?”

“I should be proud to feel that we were acting together, Mr. Holmes,” said the inspector, earnestly.

“In that case I should be glad to hear the evidence and to examine the premises without an instant of unnecessary delay.”

Inspector Martin had the good sense to allow my friend to do things in his own fashion, and contented himself with carefully noting the results. The local surgeon, an old, white-haired man, had just come down from Mrs. Hilton Cubitt’s room, and he reported that her injuries were serious, but not necessarily fatal. The bullet had passed through the front of her brain, and it would probably be some time before she could regain consciousness. On the question of whether she had been shot or had shot herself, he would not venture to express any decided opinion. Certainly the bullet had been discharged at very close quarters. There was only the one pistol found in the room, two barrels of which had been emptied. Mr. Hilton Cubitt had been shot through the heart. It was equally conceivable that he had shot her and then himself, or that she had been the criminal, for the revolver lay upon the floor midway between them.

“Has he been moved?” asked Holmes.

“We have moved nothing except the lady. We could not leave her lying wounded upon the floor.”

“How long have you been here, Doctor?”

“Since four o’clock.”

“Anyone else?”

“Yes, the constable here.”

“And you have touched nothing?”

“Nothing.”

“You have acted with great discretion. Who sent for you?”

“The housemaid, Saunders.”

“Was it she who gave the alarm?”

“She and Mrs. King, the cook.”

“Where are they now?”

“In the kitchen, I believe.”

“Then I think we had better hear their story at once.”

The old hall, oak-panelled and high-windowed, had been turned into a court of investigation. Holmes sat in a great, old-fashioned chair, his inexorable eyes gleaming out of his haggard face. I could read in them a set purpose to devote his life to this quest until the client whom he had failed to save should at last be avenged. The trim Inspector Martin, the old, gray-headed country doctor, myself, and a stolid village policeman made up the rest of that strange company.

| The Dancing Men 5 | The Dancing Men 6 |