| The Creeping Man 4 | The Creeping Man 5 |

Monday morning found us on our way to the famous university town – an easy effort on the part of Holmes, who had no roots to pull up, but one which involved frantic planning and hurrying on my part, as my practice was by this time not inconsiderable. Holmes made no allusion to the case until after we had deposited our suitcases at the ancient hostel of which he had spoken.

“I think, Watson, that we can catch the professor just before lunch. He lectures at eleven and should have an interval at home.”

“What possible excuse have we for calling?”

Holmes glanced at his notebook.

“There was a period of excitement upon August 26th. We will assume that he is a little hazy as to what he does at such times. If we insist that we are there by appointment I think he will hardly venture to contradict us. Have you the effrontery necessary to put it through?”

“We can but try.”

“Excellent, Watson! Compound of the Busy Bee and Excelsior. We can but try – the motto of the firm. A friendly native will surely guide us.”

Such a one on the back of a smart hansom swept us past a row of ancient colleges and, finally turning into a tree-lined drive, pulled up at the door of a charming house, girt round with lawns and covered with purple wisteria. Professor Presbury was certainly surrounded with every sign not only of comfort but of luxury. Even as we pulled up, a grizzled head appeared at the front window, and we were aware of a pair of keen eyes from under shaggy brows which surveyed us through large horn glasses. A moment later we were actually in his sanctum, and the mysterious scientist, whose vagaries had brought us from London, was standing before us. There was certainly no sign of eccentricity either in his manner or appearance, for he was a portly, large-featured man, grave, tall, and frock-coated, with the dignity of bearing which a lecturer needs. His eyes were his most remarkable feature, keen, observant, and clever to the verge of cunning.

He looked at our cards. “Pray sit down, gentlemen. What can I do for you?”

Mr. Holmes smiled amiably.

“It was the question which I was about to put to you, Professor.”

“To me, sir!”

“Possibly there is some mistake. I heard through a second person that Professor Presbury of Camford had need of my services.”

“Oh, indeed!” It seemed to me that there was a malicious sparkle in the intense gray eyes. “You heard that, did you? May I ask the name of your informant?”

“I am sorry, Professor, but the matter was rather confidential. If I have made a mistake there is no harm done. I can only express my regret.”

“Not at all. I should wish to go further into this matter. It interests me. Have you any scrap of writing, any letter or telegram, to bear out your assertion?”

“No, I have not.”

“I presume that you do not go so far as to assert that I summoned you?”

“I would rather answer no questions,” said Holmes.

“No, I dare say not,” said the professor with asperity. “However, that particular one can be answered very easily without your aid.”

He walked across the room to the bell. Our London friend, Mr. Bennett, answered the call.

“Come in, Mr. Bennett. These two gentlemen have come from London under the impression that they have been summoned. You handle all my correspondence. Have you a note of anything going to a person named Holmes?”

“No, sir,” Bennett answered with a flush.

“That is conclusive,” said the professor, glaring angrily at my companion. “Now, sir” – he leaned forward with his two hands upon the table – “it seems to me that your position is a very questionable one.”

Holmes shrugged his shoulders.

“I can only repeat that I am sorry that we have made a needless intrusion.”

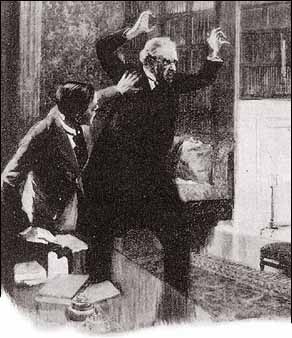

“Hardly enough, Mr. Holmes!” the old man cried in a high screaming voice, with extraordinary malignancy upon his face. He got between us and the door as he spoke, and he shook his two hands at us with furious passion. “You can hardly get out of it so easily as that.” His face was convulsed, and he grinned and gibbered at us in his senseless rage. I am convinced that we should have had to fight our way out of the room if Mr. Bennett had not intervened.

“My dear Professor,” he cried, “consider your position! Consider the scandal at the university! Mr. Holmes is a well-known man. You cannot possibly treat him with such discourtesy.”

Sulkily our host – if I may call him so – cleared the path to the door. We were glad to find ourselves outside the house and in the quiet of the tree-lined drive. Holmes seemed greatly amused by the episode.

“Our learned friend’s nerves are somewhat out of order,” said he. “Perhaps our intrusion was a little crude, and yet we have gained that personal contact which I desired. But, dear me, Watson, he is surely at our heels. The villain still pursues us.”

There were the sounds of running feet behind, but it was, to my relief, not the formidable professor but his assistant who appeared round the curve of the drive. He came panting up to us.

“I am so sorry, Mr. Holmes. I wished to apologize.”

“My dear sir, there is no need. It is all in the way of professional experience.”

“I have never seen him in a more dangerous mood. But he grows more sinister. You can understand now why his daughter and I are alarmed. And yet his mind is perfectly clear.”

“Too clear!” said Holmes. “That was my miscalculation. It is evident that his memory is much more reliable than I had thought. By the way, can we, before we go, see the window of Miss Presbury’s room?”

Mr. Bennett pushed his way through some shrubs, and we had a view of the side of the house.

“It is there. The second on the left.”

“Dear me, it seems hardly accessible. And yet you will observe that there is a creeper below and a water-pipe above which give some foothold.”

“I could not climb it myself,” said Mr. Bennett.

“Very likely. It would certainly be a dangerous exploit for any normal man.”

“There was one other thing I wish to tell you, Mr. Holmes. I have the address of the man in London to whom the professor writes. He seems to have written this morning, and I got it from his blotting-paper. It is an ignoble position for a trusted secretary, but what else can I do?”

Holmes glanced at the paper and put it into his pocket.

“Dorak – a curious name. Slavonic, I imagine. Well, it is an important link in the chain. We return to London this afternoon, Mr. Bennett. I see no good purpose to be served by our remaining. We cannot arrest the professor because he has done no crime, nor can we place him under constraint, for he cannot be proved to be mad. No action is as yet possible.”

“Then what on earth are we to do?”

“A little patience, Mr. Bennett. Things will soon develop. Unless I am mistaken, next Tuesday may mark a crisis. Certainly we shall be in Camford on that day. Meanwhile, the general position is undeniably unpleasant, and if Miss Presbury can prolong her visit– –”

“That is easy.”

“Then let her stay till we can assure her that all danger is past. Meanwhile, let him have his way and do not cross him. So long as he is in a good humour all is well.”

“There he is!” said Bennett in a startled whisper. Looking between the branches we saw the tall, erect figure emerge from the hall door and look around him. He stood leaning forward, his hands swinging straight before him, his head turning from side to side. The secretary with a last wave slipped off among the trees, and we saw him presently rejoin his employer, the two entering the house together in what seemed to be animated and even excited conversation.

“I expect the old gentleman has been putting two and two together,” said Holmes as we walked hotelward. “He struck me as having a particularly clear and logical brain from the little I saw of him. Explosive, no doubt, but then from his point of view he has something to explode about if detectives are put on his track and he suspects his own household of doing it. I rather fancy that friend Bennett is in for an uncomfortable time.”

Holmes stopped at a post-office and sent off a telegram on our way. The answer reached us in the evening, and he tossed it across to me.

Have visited the Commercial Road and seen Dorak. Suave person, Bohemian, elderly. Keeps large general store.

MERCER.

“Mercer is since your time,” said Holmes. “He is my general utility man who looks up routine business. It was important to know something of the man with whom our professor was so secretly corresponding. His nationality connects up with the Prague visit.”

“Thank goodness that something connects with something,” said I. “At present we seem to be faced by a long series of inexplicable incidents with no bearing upon each other. For example, what possible connection can there be between an angry wolfhound and a visit to Bohemia, or either of them with a man crawling down a passage at night? As to your dates, that is the biggest mystification of all.”

Holmes smiled and rubbed his hands. We were, I may say, seated in the old sitting-room of the ancient hotel, with a bottle of the famous vintage of which Holmes had spoken on the table between us.

“Well, now, let us take the dates first,” said he, his finger-tips together and his manner as if he were addressing a class. “This excellent young man’s diary shows that there was trouble upon July 2d, and from then onward it seems to have been at nine-day intervals, with, so far as I remember, only one exception. Thus the last outbreak upon Friday was on September 3d, which also falls into the series, as did August 26th, which preceded it. The thing is beyond coincidence.”

I was forced to agree.

“Let us, then, form the provisional theory that every nine days the professor takes some strong drug which has a passing but highly poisonous effect. His naturally violent nature is intensified by it. He learned to take this drug while he was in Prague, and is now supplied with it by a Bohemian intermediary in London. This all hangs together, Watson!”

“But the dog, the face at the window, the creeping man in the passage?”

“Well, well, we have made a beginning. I should not expect any fresh developments until next Tuesday. In the meantime we can only keep in touch with friend Bennett and enjoy the amenities of this charming town.”

In the morning Mr. Bennett slipped round to bring us the latest report. As Holmes had imagined, times had not been easy with him. Without exactly accusing him of being responsible for our presence, the professor had been very rough and rude in his speech, and evidently felt some strong grievance. This morning he was quite himself again, however, and had delivered his usual brilliant lecture to a crowded class. “Apart from his queer fits,” said Bennett, “he has actually more energy and vitality than I can ever remember, nor was his brain ever clearer. But it’s not he – it’s never the man whom we have known.”

“I don’t think you have anything to fear now for a week at least,” Holmes answered. “I am a busy man, and Dr. Watson has his patients to attend to. Let us agree that we meet here at this hour next Tuesday, and I shall be surprised if before we leave you again we are not able to explain, even if we cannot perhaps put an end to, your troubles. Meanwhile, keep us posted in what occurs.”

| The Creeping Man 4 | The Creeping Man 5 |