| The Blanched Soldier 2 | The Blanched Soldier 3 |

“When I joined up in January, 1901 – just two years ago – young Godfrey Emsworth had joined the same squadron. He was Colonel Emsworth’s only son – Emsworth, the Crimean V. C. – and he had the fighting blood in him, so it is no wonder he volunteered. There was not a finer lad in the regiment. We formed a friendship – the sort of friendship which can only be made when one lives the same life and shares the same joys and sorrows. He was my mate – and that means a good deal in the Army. We took the rough and the smooth together for a year of hard fighting. Then he was hit with a bullet from an elephant gun in the action near Diamond Hill outside Pretoria. I got one letter from the hospital at Cape Town and one from Southampton. Since then not a word – not one word, Mr. Holmes, for six months and more, and he my closest pal.

“Well, when the war was over, and we all got back, I wrote to his father and asked where Godfrey was. No answer. I waited a bit and then I wrote again. This time I had a reply, short and gruff. Godfrey had gone on a voyage round the world, and it was not likely that he would be back for a year. That was all.

“I wasn’t satisfied, Mr. Holmes. The whole thing seemed to me so damned unnatural. He was a good lad, and he would not drop a pal like that. It was not like him. Then, again, I happened to know that he was heir to a lot of money, and also that his father and he did not always hit it off too well. The old man was sometimes a bully, and young Godfrey had too much spirit to stand it. No, I wasn’t satisfied, and I determined that I would get to the root of the matter. It happened, however, that my own affairs needed a lot of straightening out, after two years’ absence, and so it is only this week that I have been able to take up Godfrey’s case again. But since I have taken it up I mean to drop everything in order to see it through.”

Mr. James M. Dodd appeared to be the sort of person whom it would be better to have as a friend than as an enemy. His blue eyes were stern and his square jaw had set hard as he spoke.

“Well, what have you done?” I asked.

“My first move was to get down to his home, Tuxbury Old Park, near Bedford, and to see for myself how the ground lay. I wrote to the mother, therefore – I had had quite enough of the curmudgeon of a father – and I made a clean frontal attack: Godfrey was my chum, I had a great deal of interest which I might tell her of our common experiences, I should be in the neighbourhood, would there be any objection, et cetera? In reply I had quite an amiable answer from her and an offer to put me up for the night. That was what took me down on Monday.

“Tuxbury Old Hall is inaccessible – five miles from anywhere. There was no trap at the station, so I had to walk, carrying my suitcase, and it was nearly dark before I arrived. It is a great wandering house, standing in a considerable park. I should judge it was of all sorts of ages and styles, starting on a half-timbered Elizabethan foundation and ending in a Victorian portico. Inside it was all panelling and tapestry and half-effaced old pictures, a house of shadows and mystery. There was a butler, old Ralph, who seemed about the same age as the house, and there was his wife, who might have been older. She had been Godfrey’s nurse, and I had heard him speak of her as second only to his mother in his affections, so I was drawn to her in spite of her queer appearance. The mother I liked also – a gentle little white mouse of a woman. It was only the colonel himself whom I barred.

“We had a bit of barney right away, and I should have walked back to the station if I had not felt that it might be playing his game for me to do so. I was shown straight into his study, and there I found him, a huge, bow-backed man with a smoky skin and a straggling gray beard, seated behind his littered desk. A red-veined nose jutted out like a vulture’s beak, and two fierce gray eyes glared at me from under tufted brows. I could understand now why Godfrey seldom spoke of his father.

“ ‘Well, sir,’ said he in a rasping voice, ‘I should be interested to know the real reasons for this visit.’

“I answered that I had explained them in my letter to his wife.

“ ‘Yes, yes, you said that you had known Godfrey in Africa. We have, of course, only your word for that.’

“ ‘I have his letters to me in my pocket.’

“ ‘Kindly let me see them.’

“He glanced at the two which I handed him, and then he tossed them back.

“ ‘Well, what then?’ he asked.

“ ‘I was fond of your son Godfrey, sir. Many ties and memories united us. Is it not natural that I should wonder at his sudden silence and should wish to know what has become of him?’

“ ‘I have some recollections, sir, that I had already corresponded with you and had told you what had become of him. He has gone upon a voyage round the world. His health was in a poor way after his African experiences, and both his mother and I were of opinion that complete rest and change were needed. Kindly pass that explanation on to any other friends who may be interested in the matter.’

“ ‘Certainly,’ I answered. ‘But perhaps you would have the goodness to let me have the name of the steamer and of the line by which he sailed, together with the date. I have no doubt that I should be able to get a letter through to him.’

“My request seemed both to puzzle and to irritate my host. His great eyebrows came down over his eyes, and he tapped his fingers impatiently on the table. He looked up at last with the expression of one who has seen his adversary make a dangerous move at chess, and has decided how to meet it.

“ ‘Many people, Mr. Dodd,’ said he, ‘would take offence at your infernal pertinacity and would think that this insistence had reached the point of damned impertinence.’

“ ‘You must put it down, sir, to my real love for your son.’

“ ‘Exactly. I have already made every allowance upon that score. I must ask you, however, to drop these inquiries. Every family has its own inner knowledge and its own motives, which cannot always be made clear to outsiders, however well-intentioned. My wife is anxious to hear something of Godfrey’s past which you are in a position to tell her, but I would ask you to let the present and the future alone. Such inquiries serve no useful purpose, sir, and place us in a delicate and difficult position.’

“So I came to a dead end, Mr. Holmes. There was no getting past it. I could only pretend to accept the situation and register a vow inwardly that I would never rest until my friend’s fate had been cleared up. It was a dull evening. We dined quietly, the three of us, in a gloomy, faded old room. The lady questioned me eagerly about her son, but the old man seemed morose and depressed. I was so bored by the whole proceeding that I made an excuse as soon as I decently could and retired to my bedroom. It was a large, bare room on the ground floor, as gloomy as the rest of the house, but after a year of sleeping upon the veldt, Mr. Holmes, one is not too particular about one’s quarters. I opened the curtains and looked out into the garden, remarking that it was a fine night with a bright half-moon. Then I sat down by the roaring fire with the lamp on a table beside me, and endeavoured to distract my mind with a novel. I was interrupted, however, by Ralph, the old butler, who came in with a fresh supply of coals.

“ ‘I thought you might run short in the night-time, sir. It is bitter weather and these rooms are cold.’

“He hesitated before leaving the room, and when I looked round he was standing facing me with a wistful look upon his wrinkled face.

“ ‘Beg your pardon, sir, but I could not help hearing what you said of young Master Godfrey at dinner. You know, sir, that my wife nursed him, and so I may say I am his foster-father. It’s natural we should take an interest. And you say he carried himself well, sir?’

“ ‘There was no braver man in the regiment. He pulled me out once from under the rifles of the Boers, or maybe I should not be here.’

“The old butler rubbed his skinny hands.

“ ‘Yes, sir, yes, that is Master Godfrey all over. He was always courageous. There’s not a tree in the park, sir, that he has not climbed. Nothing would stop him. He was a fine boy – and oh, sir, he was a fine man.’

“I sprang to my feet.

“ ‘Look here!’ I cried. ‘You say he was. You speak as if he were dead. What is all this mystery? What has become of Godfrey Emsworth?’

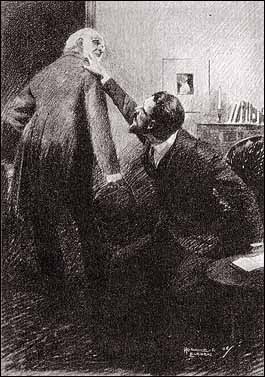

“I gripped the old man by the shoulder, but he shrank away.

“ ‘I don’t know what you mean, sir. Ask the master about Master Godfrey. He knows. It is not for me to interfere.’

“He was leaving the room, but I held his arm.

“ ‘Listen,’ I said. ‘You are going to answer one question before you leave if I have to hold you all night. Is Godfrey dead?’

“He could not face my eyes. He was like a man hypnotized. The answer was dragged from his lips. It was a terrible and unexpected one.

“ ‘I wish to God he was!’ he cried, and, tearing himself free, he dashed from the room.

| The Blanched Soldier 2 | The Blanched Soldier 3 |