“He’s a fine fellow,” said Holmes as we came out into Whitehall. “But he has a struggle to keep up his position. He is far from rich and has many calls. You noticed, of course, that his boots had been resoled. Now, Watson, I won’t detain you from your legitimate work any longer. I shall do nothing more to-day unless I have an answer to my cab advertisement. But I should be extremely obliged to you if you would come down with me to Woking to-morrow by the same train which we took yesterday.”

I met him accordingly next morning and we travelled down to Woking together. He had had no answer to his advertisement, he said, and no fresh light had been thrown upon the case. He had, when he so willed it, the utter immobility of countenance of a red Indian, and I could not gather from his appearance whether he was satisfied or not with the position of the case. His conversation, I remember, was about the Bertillon system of measurements, and he expressed his enthusiastic admiration of the French savant.

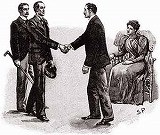

We found our client still under the charge of his devoted nurse, but looking considerably better than before. He rose from the sofa and greeted us without difficulty when we entered.

“Any news?” he asked eagerly.

“My report, as I expected, is a negative one,” said Holmes. “I have seen Forbes, and I have seen your uncle, and I have set one or two trains of inquiry upon foot which may lead to something.”

“You have not lost heart, then?”

“By no means.”

“God bless you for saying that!” cried Miss Harrison. “If we keep our courage and our patience the truth must come out.”

“We have more to tell you than you have for us,” said Phelps, reseating himself upon the couch.

“I hoped you might have something.”

“Yes, we have had an adventure during the night, and one which might have proved to be a serious one.” His expression grew very grave as he spoke, and a look of something akin to fear sprang up in his eyes. “Do you know,” said he, “that I begin to believe that I am the unconscious centre of some monstrous conspiracy, and that my life is aimed at as well as my honour?”

“Ah!” cried Holmes.

“It sounds incredible, for I have not, as far as I know, an enemy in the world. Yet from last night’s experience I can come to no other conclusion.”

“Pray let me hear it.”

“You must know that last night was the very first night that I have ever slept without a nurse in the room. I was so much better that I though I could dispense with one. I had a night-light burning, however. Well, about two in the morning I had sunk into a light sleep when I was suddenly aroused by a slight noise. It was like the sound which a mouse makes when it is gnawing a plank, and I lay listening to it for some time under the impression that it must come from that cause. Then it grew louder, and suddenly there came from the window a sharp metallic snick. I sat up in amazement. There could be no doubt what the sounds were now. The first ones had been caused by someone forcing an instrument through the slit between the sashes, and the second by the catch being pressed back.

“There was a pause then for about ten minutes, as if the person were waiting to see whether the noise had awakened me. Then I heard a gentle creaking as the window was very slowly opened. I could stand it no longer, for my nerves are not what they used to be. I sprang out of bed and flung open the shutters. A man was crouching at the window. I could see little of him, for he was gone like a flash. He was wrapped in some sort of cloak which came across the lower part of his face. One thing only I am sure of, and that is that he had some weapon in his hand. It looked to me like a long knife. I distinctly saw the gleam of it as he turned to run.”