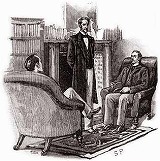

We were fortunate in finding that Lord Holdhurst was still in his chambers in Downing Street, and on Holmes sending in his card we were instantly shown up. The statesman received us with that old-fashioned courtesy for which he is remarkable and seated us on the two luxuriant lounges on either side of the fireplace. Standing on the rug between us, with his slight, tall figure, his sharp features, thoughtful face, and curling hair prematurely tinged with gray, he seemed to represent that not too common type, a nobleman who is in truth noble.

“Your name is very familiar to me, Mr. Holmes,” said he, smiling. “And of course I cannot pretend to be ignorant of the object of your visit. There has only been one occurrence in these offices which could call for your attention. In whose interest are you acting, may I ask?”

“In that of Mr. Percy Phelps,” answered Holmes.

“Ah, my unfortunate nephew! You can understand that our kinship makes it the more impossible for me to screen him in any way. I fear that the incident must have a very prejudicial effect upon his career.”

“But if the document is found?”

“Ah, that, of course, would be different.”

“I had one or two questions which I wished to ask you, Lord Holdhurst.”

“I shall be happy to give you any information in my power.”

“Was it in this room that you gave your instructions as to the copying of the document?”

“It was.”

“Then you could hardly have been overheard?”

“It is out of the question.”

“Did you ever mention to anyone that it was your intention to give anyone the treaty to be copied?”

“Never.”

“You are certain of that?”

“Absolutely.”

“Well, since you never said so, and Mr. Phelps never said so, and nobody else knew anything of the matter, then the thief’s presence in the room was purely accidental. He saw his chance and he took it.”

The statesman smiled. “You take me out of my province there,” said he.

Holmes considered for a moment. “There is another very important point which I wish to discuss with you,” said he. “You feared, as I understand, that very grave results might follow from the details of this treaty becoming known.”

A shadow passed over the expressive face of the statesman. “Very grave results indeed.”

“And have they occurred?”

“Not yet.”

“If the treaty had reached, let us say, the French or Russian Foreign Office, you would expect to hear of it?”

“I should,” said Lord Holdhurst with a wry face.

“Since nearly ten weeks have elapsed, then, and nothing has been heard, it is not unfair to suppose that for some reason the treaty has not reached them.”

Lord Holdhurst shrugged his shoulders.

“We can hardly suppose, Mr. Holmes, that the thief took the treaty in order to frame it and hang it up.”

“Perhaps he is waiting for a better price.”

“If he waits a little longer he will get no price at all. The treaty will cease to be secret in a few months.”

“That is most important,” said Holmes. “Of course, it is a possible supposition that the thief has had a sudden illness- -”

“An attack of brain-fever, for example?” asked the statesman, flashing a swift glance at him.

“I did not say so,” said Holmes imperturbably. “And now, Lord Holdhurst, we have already taken up too much of your valuable time, and we shall wish you good-day.”

“Every success to your investigation, be the criminal who it may,” answered the nobleman as he bowed us out at the door.