A COLD and melancholy walk of a couple of miles brought us to a high wooden gate, which opened into a gloomy avenue of chestnuts. The curved and shadowed drive led us to a low, dark house, pitch-black against a slate-coloured sky. From the front window upon the left of the door there peeped a glimmer of a feeble light.

“There’s a constable in possession,” said Baynes. “I’ll knock at the window.” He stepped across the grass plot and tapped with his hand on the pane. Through the fogged glass I dimly saw a man spring up from a chair beside the fire, and heard a sharp cry from within the room. An instant later a white-faced, hard-breathing policeman had opened the door, the candle wavering in his trembling hand.

“What’s the matter, Walters?” asked Baynes sharply.

The man mopped his forehead with his handkerchief and gave a long sigh of relief.

“I am glad you have come, sir. It has been a long evening, and I don’t think my nerve is as good as it was.”

“Your nerve, Walters? I should not have thought you had a nerve in your body.”

“Well, sir, it’s this lonely, silent house and the queer thing in the kitchen. Then when you tapped at the window I thought it had come again.”

“That what had come again?”

“The devil, sir, for all I know. It was at the window.”

“What was at the window, and when?”

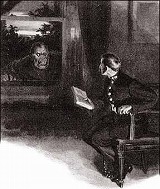

“It was just about two hours ago. The light was just fading. I was sitting reading in the chair. I don’t know what made me look up, but there was a face looking in at me through the lower pane. Lord, sir, what a face it was! I’ll see it in my dreams.”

“Tut, tut, Walters. This is not talk for a police-constable.”

“I know, sir, I know; but it shook me, sir, and there’s no use to deny it. It wasn’t black, sir, nor was it white, nor any colour that I know, but a kind of queer shade like clay with a splash of milk in it. Then there was the size of it - it was twice yours, sir. And the look of it - the great staring goggle eyes, and the line of white teeth like a hungry beast. I tell you, sir, I couldn’t move a finger, nor get my breath, till it whisked away and was gone. Out I ran and through the shrubbery, but thank God there was no one there.”

“If I didn’t know you were a good man, Walters, I should put a black mark against you for this. If it were the devil himself a constable on duty should never thank God that he could not lay his hands upon him. I suppose the whole thing is not a vision and a touch of nerves?”

“That, at least, is very easily settled,” said Holmes, lighting his little pocket lantern. “Yes,” he reported, after a short examination of the grass bed, “a number twelve shoe, I should say. If he was all on the same scale as his foot he must certainly have been a giant.”

“What became of him?”

“He seems to have broken through the shrubbery and made for the road.”

“Well,” said the inspector with a grave and thoughtful face, “whoever he may have been, and whatever he may have wanted, he’s gone for the present, and we have more immediate things to attend to. Now, Mr. Holmes, with your permission, I will show you round the house.”

The various bedrooms and sitting-rooms had yielded nothing to a careful search. Apparently the tenants had brought little or nothing with them, and all the furniture down to the smallest details had been taken over with the house. A good deal of clothing with the stamp of Marx and Co., High Holborn, had been left behind. Telegraphic inquiries had been already made which showed that Marx knew nothing of his customer save that he was a good payer. Odds and ends, some pipes, a few novels, two of them in Spanish, an old-fashioned pinfire revolver, and a guitar were among the personal property.