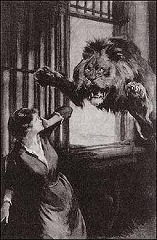

“And then the terrible thing happened. You may have heard how quick these creatures are to scent human blood, and how it excites them. Some strange instinct had told the creature in one instant that a human being had been slain. As I slipped the bars it bounded out and was on me in an instant. Leonardo could have saved me. If he had rushed forward and struck the beast with his club he might have cowed it. But the man lost his nerve. I heard him shout in his terror, and then I saw him turn and fly. At the same instant the teeth of the lion met in my face. Its hot, filthy breath had already poisoned me and I was hardly conscious of pain. With the palms of my hands I tried to push the great steaming, blood-stained jaws away from me, and I screamed for help. I was conscious that the camp was stirring, and then dimly I remembered a group of men. Leonardo, Griggs, and others, dragging me from under the creature’s paws. That was my last memory, Mr. Holmes, for many a weary month. When I came to myself and saw myself in the mirror, I cursed that lion - oh, how I cursed him! - not because he had torn away my beauty but because he had not torn away my life. I had but one desire, Mr. Holmes, and I had enough money to gratify it. It was that I should cover myself so that my poor face should be seen by none, and that I should dwell where none whom I had ever known should find me. That was all that was left to me to do - and that is what I have done. A poor wounded beast that has crawled into its hole to die - that is the end of Eugenia Ronder.”

We sat in silence for some time after the unhappy woman had told her story. Then Holmes stretched out his long arm and patted her hand with such a show of sympathy as I had seldom known him to exhibit.

“Poor girl!” he said. “Poor girl! The ways of fate are indeed hard to understand. If there is not some compensation hereafter, then the world is a cruel jest. But what of this man Leonardo?”

“I never saw him or heard from him again. Perhaps I have been wrong to feel so bitterly against him. He might as soon have loved one of the freaks whom we carried round the country as the thing which the lion had left. But a woman’s love is not so easily set aside. He had left me under the beast’s claws, he had deserted me in my need, and yet I could not bring myself to give him to the gallows. For myself, I cared nothing what became of me. What could be more dreadful than my actual life? But I stood between Leonardo and his fate.”

“And he is dead?”

“He was drowned last month when bathing near Margate. I saw his death in the paper.”

“And what did he do with this five-clawed club, which is the most singular and ingenious part of all your story?”

“I cannot tell, Mr. Holmes. There is a chalk-pit by the camp, with a deep green pool at the base of it. Perhaps in the depths of that pool- -”

“Well, well, it is of little consequence now. The case is closed.”

“Yes,” said the woman, “the case is closed.”

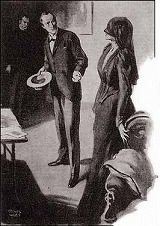

We had risen to go, but there was something in the woman’s voice which arrested Holmes’s attention. He turned swiftly upon her.

“Your life is not your own,” he said. “Keep your hands off it.”

“What use is it to anyone?”

“How can you tell? The example of patient suffering is in itself the most precious of all lessons to an impatient world.”

The woman’s answer was a terrible one. She raised her veil and stepped forward into the light.

“I wonder if you would bear it,” she said.