DANGER

IT WAS the height of the reign of terror. McMurdo, who had already been appointed Inner Deacon, with every prospect of some day succeeding McGinty as Bodymaster, was now so necessary to the councils of his comrades that nothing was done without his help and advice. The more popular he became, however, with the Freemen, the blacker were the scowls which greeted him as he passed along the streets of Vermissa. In spite of their terror the citizens were taking heart to band themselves together against their oppressors. Rumours had reached the lodge of secret gatherings in the Herald office and of distribution of firearms among the law-abiding people. But McGinty and his men were undisturbed by such reports. They were numerous, resolute, and well armed. Their opponents were scattered and powerless. It would all end, as it had done in the past, in aimless talk and possibly in impotent arrests. So said McGinty, McMurdo, and all the bolder spirits.

It was a Saturday evening in May. Saturday was always the lodge night, and McMurdo was leaving his house to attend it when Morris, the weaker brother of the order, came to see him. His brow was creased with care, and his kindly face was drawn and haggard.

“Can I speak with you freely, Mr. McMurdo?”

“Sure.”

“I can’t forget that I spoke my heart to you once, and that you kept it to yourself, even though the Boss himself came to ask you about it.”

“What else could I do if you trusted me? It wasn’t that I agreed with what you said.”

“I know that well. But you are the one that I can speak to and be safe. I’ve a secret here,” he put his hand to his breast, “and it is just burning the life out of me. I wish it had come to any one of you but me. If I tell it, it will mean murder, for sure. If I don’t, it may bring the end of us all. God help me, but I am near out of my wits over it!”

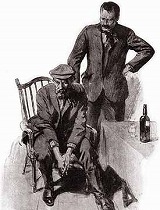

McMurdo looked at the man earnestly. He was trembling in every limb. He poured some whisky into a glass and handed it to him. “That’s the physic for the likes of you,” said he. “Now let me hear of it.”

Morris drank, and his white face took a tinge of colour. “I can tell it to you all in one sentence,” said he. “There’s a detective on our trail.”

McMurdo stared at him in astonishment. “Why, man, you’re crazy,” he said. “Isn’t the place full of police and detectives, and what harm did they ever do us?”

“No, no, it’s no man of the district. As you say, we know them, and it is little that they can do. But you’ve heard of Pinkerton’s?”

“I’ve read of some folk of that name.”

“Well, you can take it from me you’ve no show when they are on your trail. It’s not a take-it-or-miss-it government concern. It’s a dead earnest business proposition that’s out for results and keeps out till by hook or crook it gets them. If a Pinkerton man is deep in this business, we are all destroyed.”

“We must kill him.”

“Ah, it’s the first thought that came to you! So it will be up at the lodge. Didn’t I say to you that it would end in murder?”

“Sure, what is murder? Isn’t it common enough in these parts?”

“It is, indeed; but it’s not for me to point out the man that is to be murdered. I’d never rest easy again. And yet it’s our own necks that may be at stake. In God’s name what shall I do?” He rocked to and fro in his agony of indecision.

But his words had moved McMurdo deeply. It was easy to see that he shared the other’s opinion as to the danger, and the need for meeting it. He gripped Morris’s shoulder and shook him in his earnestness.