“There was some sign of violence on the stonework of the bridge - a perfectly fresh chip just opposite the body. Could you suggest any possible explanation of that?”

“Surely it must be a mere coincidence.”

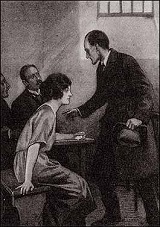

“Curious, Miss Dunbar, very curious. Why should it appear at the very time of the tragedy, and why at the very place?”

“But what could have caused it? Only great violence could have such an effect.”

Holmes did not answer. His pale, eager face had suddenly assumed that tense, far-away expression which I had learned to associate with the supreme manifestations of his genius. So evident was the crisis in his mind that none of us dared to speak, and we sat, barrister, prisoner, and myself, watching him in a concentrated and absorbed silence. Suddenly he sprang from his chair, vibrating with nervous energy and the pressing need for action.

“Come, Watson, come!” he cried.

“What is it, Mr. Holmes?”

“Never mind, my dear lady. You will hear from me, Mr. Cummings. With the help of the god of justice I will give you a case which will make England ring. You will get news by to-morrow, Miss Dunbar, and meanwhile take my assurance that the clouds are lifting and that I have every hope that the light of truth is breaking through.”

It was not a long journey from Winchester to Thor Place, but it was long to me in my impatience, while for Holmes it was evident that it seemed endless; for, in his nervous restlessness, he could not sit still, but paced the carriage or drummed with his long, sensitive fingers upon the cushions beside him. Suddenly, however, as we neared our destination he seated himself opposite to me - we had a first-class carriage to ourselves - and laying a hand upon each of my knees he looked into my eyes with the peculiarly mischievous gaze which was characteristic of his more imp-like moods.

“Watson,” said he, “I have some recollection that you go armed upon these excursions of ours.”

It was as well for him that I did so, for he took little care for his own safety when his mind was once absorbed by a problem, so that more than once my revolver had been a good friend in need. I reminded him of the fact.

“Yes, yes, I am a little absent-minded in such matters. But have you your revolver on you?”

I produced it from my hip-pocket, a short, handy, but very serviceable little weapon. He undid the catch, shook out the cartridges, and examined it with care.

“It’s heavy - remarkably heavy,” said he.

“Yes, it is a solid bit of work.”

He mused over it for a minute.

“Do you know, Watson,” said he, “I believe your revolver is going to have a very intimate connection with the mystery which we are investigating.”

“My dear Holmes, you are joking.”

“No, Watson, I am very serious. There is a test before us. If the test comes off, all will be clear. And the test will depend upon the conduct of this little weapon. One cartridge out. Now we will replace the other five and put on the safety-catch. So! That increases the weight and makes it a better reproduction.”

I had no glimmer of what was in his mind, nor did he enlighten me, but sat lost in thought until we pulled up in the little Hampshire station. We secured a ramshackle trap, and in a quarter of an hour were at the house of our confidential friend, the sergeant.

“A clue, Mr. Holmes? What is it?”

“It all depends upon the behaviour of Dr. Watson’s revolver,” said my friend. “Here it is. Now, officer, can you give me ten yards of string?”

The village shop provided a ball of stout twine.

“I think that this is all we will need,” said Holmes. “Now, if you please, we will get off on what I hope is the last stage of our journey.”