OUR prisoner’s furious resistance did not apparently indicate any ferocity in his disposition towards ourselves, for on finding himself powerless, he smiled in an affable manner, and expressed his hopes that he had not hurt any of us in the scuffle. “I guess you’re going to take me to the police-station,” he remarked to Sherlock Holmes. “My cab’s at the door. If you’ll loose my legs I’ll walk down to it. I’m not so light to lift as I used to be.”

Gregson and Lestrade exchanged glances, as if they thought this proposition rather a bold one; but Holmes at once took the prisoner at his word, and loosened the towel which we had bound round his ankles. He rose and stretched his legs, as though to assure himself that they were free once more. I remember that I thought to myself, as I eyed him, that I had seldom seen a more powerfully built man; and his dark, sunburned face bore an expression of determination and energy which was as formidable as his personal strength.

“If there’s a vacant place for a chief of the police, I reckon you are the man for it,” he said, gazing with undisguised admiration at my fellow-lodger. “The way you kept on my trail was a caution.”

“You had better come with me,” said Holmes to the two detectives.

“I can drive you,” said Lestrade.

“Good! and Gregson can come inside with me. You too, Doctor. You have taken an interest in the case, and may as well stick to us.”

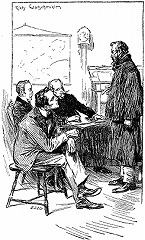

I assented gladly, and we all descended together. Our prisoner made no attempt at escape, but stepped calmly into the cab which had been his, and we followed him. Lestrade mounted the box, whipped up the horse, and brought us in a very short time to our destination. We were ushered into a small chamber, where a police inspector noted down our prisoner’s name and the names of the men with whose murder he had been charged. The official was a white-faced, unemotional man, who went through his duties in a dull, mechanical way. “The prisoner will be put before the magistrates in the course of the week,” he said; “in the meantime, Mr. Jefferson Hope, have you anything that you wish to say? I must warn you that your words will be taken down, and may be used against you.”

“I’ve got a good deal to say,” our prisoner said slowly. “I want to tell you gentlemen all about it.”

“Hadn’t you better reserve that for your trial?” asked the inspector.

“I may never be tried,” he answered. “You needn’t look startled. It isn’t suicide I am thinking of. Are you a doctor?” He turned his fierce dark eyes upon me as he asked this last question.

“Yes, I am,” I answered.

“Then put your hand here,” he said, with a smile, motioning with his manacled wrists towards his chest.

I did so; and became at once conscious of an extraordinary throbbing and commotion which was going on inside. The walls of his chest seemed to thrill and quiver as a frail building would do inside when some powerful engine was at work. In the silence of the room I could hear a dull humming and buzzing noise which proceeded from the same source.

“Why,” I cried, “you have an aortic aneurism!”

“That’s what they call it,” he said, placidly. “I went to a doctor last week about it, and he told me that it is bound to burst before many days passed. It has been getting worse for years. I got it from overexposure and under-feeding among the Salt Lake Mountains. I’ve done my work now, and I don’t care how soon I go, but I should like to leave some account of the business behind me. I don’t want to be remembered as a common cut-throat.”

The inspector and the two detectives had a hurried discussion as to the advisability of allowing him to tell his story.

“Do you consider, Doctor, that there is immediate danger?” the former asked.