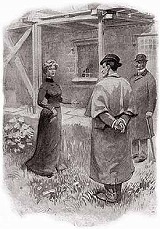

“I thought it as well,” said Holmes as we climbed the stile, “that this fellow should think we had come here as architects, or on some definite business. It may stop his gossip. Good-afternoon, Miss Stoner. You see that we have been as good as our word.”

Our client of the morning had hurried forward to meet us with a face which spoke her joy. “I have been waiting so eagerly for you,” she cried, shaking hands with us warmly. “All has turned out splendidly. Dr. Roylott has gone to town, and it is unlikely that he will be back before evening.”

“We have had the pleasure of making the doctor’s acquaintance,” said Holmes, and in a few words he sketched out what had occurred. Miss Stoner turned white to the lips as she listened.

“Good heavens!” she cried, “he has followed me, then.”

“So it appears.”

“He is so cunning that I never know when I am safe from him. What will he say when he returns?”

“He must guard himself, for he may find that there is someone more cunning than himself upon his track. You must lock yourself up from him to-night. If he is violent, we shall take you away to your aunt’s at Harrow. Now, we must make the best use of our time, so kindly take us at once to the rooms which we are to examine.”

The building was of gray, lichen-blotched stone, with a high central portion and two curving wings, like the claws of a crab, thrown out on each side. In one of these wings the windows were broken and blocked with wooden boards, while the roof was partly caved in, a picture of ruin. The central portion was in little better repair, but the right-hand block was comparatively modern, and the blinds in the windows, with the blue smoke curling up from the chimneys, showed that this was where the family resided. Some scaffolding had been erected against the end wall, and the stone-work had been broken into, but there were no signs of any workmen at the moment of our visit. Holmes walked slowly up and down the ill-trimmed lawn and examined with deep attention the outsides of the windows.

“This, I take it, belongs to the room in which you used to sleep, the centre one to your sister’s, and the one next to the main building to Dr. Roylott’s chamber?”

“Exactly so. But I am now sleeping in the middle one.”

“Pending the alterations, as I understand. By the way, there does not seem to be any very pressing need for repairs at that end wall.”

“There were none. I believe that it was an excuse to move me from my room.”

“Ah! that is suggestive. Now, on the other side of this narrow wing runs the corridor from which these three rooms open. There are windows in it, of course?”

“Yes, but very small ones. Too narrow for anyone to pass through.”

“As you both locked your doors at night, your rooms were unapproachable from that side. Now, would you have the kindness to go into your room and bar your shutters?”

Miss Stoner did so, and Holmes, after a careful examination through the open window, endeavoured in every way to force the shutter open, but without success. There was no slit through which a knife could be passed to raise the bar. Then with his lens he tested the hinges, but they were of solid iron, built firmly into the massive masonry. “Hum!” said he, scratching his chin in some perplexity, “my theory certainly presents some difficulties. No one could pass these shutters if they were bolted. Well, we shall see if the inside throws any light upon the matter.”