The spot where the fragments of the bust had been found was only a few hundred yards away. For the first time our eyes rested upon this presentment of the great emperor, which seemed to raise such frantic and destructive hatred in the mind of the unknown. It lay scattered, in splintered shards, upon the grass. Holmes picked up several of them and examined them carefully. I was convinced, from his intent face and his purposeful manner, that at last he was upon a clue.

“Well?” asked Lestrade.

Holmes shrugged his shoulders.

“We have a long way to go yet,” said he. “And yet - and yet - well, we have some suggestive facts to act upon. The possession of this trifling bust was worth more, in the eyes of this strange criminal, than a human life. That is one point. Then there is the singular fact that he did not break it in the house, or immediately outside the house, if to break it was his sole object.”

“He was rattled and bustled by meeting this other fellow. He hardly knew what he was doing.”

“Well, that’s likely enough. But I wish to call your attention very particularly to the position of this house, in the garden of which the bust was destroyed.”

Lestrade looked about him.

“It was an empty house, and so he knew that he would not be disturbed in the garden.”

“Yes, but there is another empty house farther up the street which he must have passed before he came to this one. Why did he not break it there, since it is evident that every yard that he carried it increased the risk of someone meeting him?”

“I give it up,” said Lestrade.

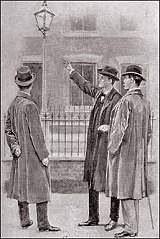

Holmes pointed to the street lamp above our heads.

“He could see what he was doing here, and he could not there. That was his reason.”

“By Jove! that’s true,” said the detective. “Now that I come to think of it, Dr. Barnicot’s bust was broken not far from his red lamp. Well, Mr. Holmes, what are we to do with that fact?”

“To remember it - to docket it. We may come on something later which will bear upon it. What steps do you propose to take now, Lestrade?”

“The most practical way of getting at it, in my opinion, is to identify the dead man. There should be no difficulty about that. When we have found who he is and who his associates are, we should have a good start in learning what he was doing in Pitt Street last night, and who it was who met him and killed him on the doorstep of Mr. Horace Harker. Don’t you think so?”

“No doubt; and yet it is not quite the way in which I should approach the case.”

“What would you do then?”

“Oh, you must not let me influence you in any way. I suggest that you go on your line and I on mine. We can compare notes afterwards, and each will supplement the other.”

“Very good,” said Lestrade.

“If you are going back to Pitt Street, you might see Mr. Horace Harker. Tell him for me that I have quite made up my mind, and that it is certain that a dangerous homicidal lunatic, with Napoleonic delusions, was in his house last night. It will be useful for his article.”

Lestrade stared.

“You don’t seriously believe that?”

Holmes smiled.