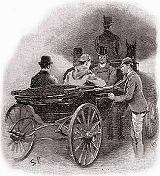

As we stepped into the carriage one of the stable-lads held the door open for us. A sudden idea seemed to occur to Holmes, for he leaned forward and touched the lad upon the sleeve.

“You have a few sheep in the paddock,” he said. “Who attends to them?”

“I do, sir.”

“Have you noticed anything amiss with them of late?”

“Well, sir, not of much account, but three of them have gone lame, sir.”

I could see that Holmes was extremely pleased, for he chuckled and rubbed his hands together.

“A long shot, Watson, a very long shot,” said he, pinching my arm. “Gregory, let me recommend to your attention this singular epidemic among the sheep. Drive on, coachman!”

Colonel Ross still wore an expression which showed the poor opinion which he had formed of my companion’s ability, but I saw by the inspector’s face that his attention had been keenly aroused.

“You consider that to be important?” he asked.

“Exceedingly so.”

“Is there any point to which you would wish to draw my attention?”

“To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.”

“The dog did nothing in the night-time.”

“That was the curious incident,” remarked Sherlock Holmes.

Four days later Holmes and I were again in the train, bound for Winchester to see the race for the Wessex Cup. Colonel Ross met us by appointment outside the station, and we drove in his drag to the course beyond the town. His face was grave, and his manner was cold in the extreme.

“I have seen nothing of my horse,” said he.

“I suppose that you would know him when you saw him?” asked Holmes.

The colonel was very angry. “I have been on the turf for twenty years and never was asked such a question as that before,” said he. “A child would know Silver Blaze with his white forehead and his mottled off-foreleg.”

“How is the betting?”

“Well, that is the curious part of it. You could have got fifteen to one yesterday, but the price has become shorter and shorter, until you can hardly get three to one now.”

“Hum!” said Holmes. “Somebody knows something, that is clear.”

As the drag drew up in the enclosure near the grandstand I glanced at the card to see the entries.

Wessex Plate [it ran] 50 sovs. each h ft with 1000 sovs. added, for four and five year olds. Second, £300. Third, £200. New course (one mile and five furlongs).

1. Mr. Heath Newton’s The Negro. Red cap. Cinnamon jacket.

2. Colonel Wardlaw’s Pugilist. Pink cap. Blue and black jacket.

3. Lord Backwater’s Desborough. Yellow cap and sleeves.

4. Colonel Ross’s Silver Blaze. Black cap. Red jacket.

5. Duke of Balmoral’s Iris. Yellow and black stripes.

6. Lord Singleford’s Rasper. Purple cap. Black sleeves.

“We scratched our other one and put all hopes on your word,” said the colonel. “Why, what is that? Silver Blaze favourite?”

“Five to four against Silver Blaze!” roared the ring. “Five to four against Silver Blaze! Five to fifteen against Desborough! Five to four on the field!”

“There are the numbers up,” I cried. “They are all six there.”

“All six there? Then my horse is running,” cried the colonel in great agitation. “But I don’t see him. My colours have not passed.”

“Only five have passed. This must be he.”

As I spoke a powerful bay horse swept out from the weighing enclosure and cantered past us, bearing on its back the well-known black and red of the colonel.

“That’s not my horse,” cried the owner. “That beast has not a white hair upon its body. What is this that you have done, Mr. Holmes?”