“I don’t know that I have anything else to tell you. I had heard a waterman speak of the speed of Smith’s launch, the Aurora, so I thought she would be a handy craft for our escape. I engaged with old Smith, and was to give him a big sum if he got us safe to our ship. He knew, no doubt, that there was some screw loose, but he was not in our secrets. All this is the truth, and if I tell it to you, gentlemen, it is not to amuse you - for you have not done me a very good turn - but it is because I believe the best defence I can make is just to hold back nothing, but let all the world know how badly I have myself been served by Major Sholto, and how innocent I am of the death of his son.”

“A very remarkable account,” said Sherlock Holmes. “A fitting windup to an extremely interesting case. There is nothing at all new to me in the latter part of your narrative except that you brought your own rope. That I did not know. By the way, I had hoped that Tonga had lost all his darts; yet he managed to shoot one at us in the boat.”

“He had lost them all, sir, except the one which was in his blow-pipe at the time.”

“Ah, of course,” said Holmes. “I had not thought of that.”

“Is there any other point which you would like to ask about?” asked the convict affably.

“I think not, thank you,” my companion answered.

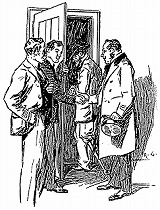

“Well, Holmes,” said Athelney Jones, “you are a man to be humoured, and we all know that you are a connoisseur of crime; but duty is duty, and I have gone rather far in doing what you and your friend asked me. I shall feel more at ease when we have our story-teller here safe under lock and key. The cab still waits, and there are two inspectors downstairs. I am much obliged to you both for your assistance. Of course you will be wanted at the trial. Good-night to you.”

“Good-night, gentlemen both,” said Jonathan Small.

“You first, Small,” remarked the wary Jones as they left the room. “I’ll take particular care that you don’t club me with your wooden leg, whatever you may have done to the gentleman at the Andaman Isles.”

“Well, and there is the end of our little drama,” I remarked, after we had sat some time smoking in silence. “I fear that it may be the last investigation in which I shall have the chance of studying your methods. Miss Morstan has done me the honour to accept me as a husband in prospective.”

He gave a most dismal groan.

“I feared as much,” said he. “I really cannot congratulate you.”

I was a little hurt.

“Have you any reason to be dissatisfied with my choice?” I asked.

“Not at all. I think she is one of the most charming young ladies I ever met and might have been most useful in such work as we have been doing. She had a decided genius that way; witness the way in which she preserved that Agra plan from all the other papers of her father. But love is an emotional thing, and whatever is emotional is opposed to that true cold reason which I place above all things. I should never marry myself, lest I bias my judgment.”

“I trust,” said I, laughing, “that my judgment may survive the ordeal. But you look weary.”

“Yes, the reaction is already upon me. I shall be as limp as a rag for a week.”

“Strange,” said I, “how terms of what in another man I should call laziness alternate with your fits of splendid energy and vigour.”

“Yes,” he answered, “there are in me the makings of a very fine loafer, and also of a pretty spry sort of a fellow. I often think of those lines of old Goethe:

”Schade, daß die Natur nur einen Mensch aus dir schuf, Denn zum würdigen Mann war und zum Schelmen der Stoff.