“It was to him himself I was to tell it,” said he.

“But I tell you that I am acting for him. Was it about Mordecai Smith’s boat?”

“Yes. I knows well where it is. An’ I knows where the men he is after are. An’ I knows where the treasure is. I knows all about it.”

“Then tell me, and I shall let him know.”

“It was to him I was to tell it,” he repeated with the petulant obstinacy of a very old man.

“Well, you must wait for him.”

“No, no; I ain’t goin’ to lose a whole day to please no one. If Mr. Holmes ain’t here, then Mr. Holmes must find it all out for himself. I don’t care about the look of either of you, and I won’t tell a word.”

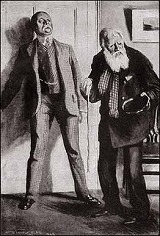

He shuffled towards the door, but Athelney Jones got in front of him.

“Wait a bit, my friend,” said he. “You have important information, and you must not walk off. We shall keep you, whether you like or not, until our friend returns.”

The old man made a little run towards the door, but, as Athelney Jones put his broad back up against it, he recognized the uselessness of resistance.

“Pretty sort o’ treatment this!” he cried, stamping his stick. “I come here to see a gentleman, and you two, who I never saw in my life, seize me and treat me in this fashion!”

“You will be none the worse,” I said. “We shall recompense you for the loss of your time. Sit over here on the sofa, and you will not have long to wait.”

He came across sullenly enough and seated himself with his face resting on his hands. Jones and I resumed our cigars and our talk. Suddenly, however, Holmes’s voice broke in upon us.

“I think that you might offer me a cigar too,” he said.

We both started in our chairs. There was Holmes sitting close to us with an air of quiet amusement.

“Holmes!” I exclaimed. “You here! But where is the old man?”

“Here is the old man,” said he, holding out a heap of white hair. “Here he is - wig, whiskers, eyebrows, and all. I thought my disguise was pretty good, but I hardly expected that it would stand that test.”

“Ah, you rogue!” cried Jones, highly delighted. “You would have made an actor and a rare one. You had the proper workhouse cough, and those weak legs of yours are worth ten pound a week. I thought I knew the glint of your eye, though. You didn’t get away from us so easily, you see.”

“I have been working in that get-up all day,” said he, lighting his cigar. “You see, a good many of the criminal classes begin to know me - especially since our friend here took to publishing some of my cases: so I can only go on the war-path under some simple disguise like this. You got my wire?”

“Yes; that was what brought me here.”

“How has your case prospered?”

“It has all come to nothing. I have had to release two of my prisoners, and there is no evidence against the other two.”

“Never mind. We shall give you two others in the place of them. But you must put yourself under my orders. You are welcome to all the official credit, but you must act on the lines that I point out. Is that agreed?”

“Entirely, if you will help me to the men.”

“Well, then, in the first place I shall want a fast police-boat - a steam launch - to be at the Westminster Stairs at seven o’clock.”

“That is easily managed. There is always one about there, but I can step across the road and telephone to make sure.”

“Then I shall want two staunch men in case of resistance.”

“There will be two or three in the boat. What else?”