“The official police don’t need you, Mr. Holmes, to tell them that the carpet must have been turned round. That’s clear enough, for the stains lie above each other - if you lay it over this way. But what I want to know is, who shifted the carpet, and why?”

I could see from Holmes’s rigid face that he was vibrating with inward excitement.

“Look here, Lestrade,” said he, “has that constable in the passage been in charge of the place all the time?”

“Yes, he has.”

“Well, take my advice. Examine him carefully. Don’t do it before us. We’ll wait here. You take him into the back room. You’ll be more likely to get a confession out of him alone. Ask him how he dared to admit people and leave them alone in this room. Don’t ask him if he has done it. Take it for granted. Tell him you know someone has been here. Press him. Tell him that a full confession is his only chance of forgiveness. Do exactly what I tell you!”

“By George, if he knows I’ll have it out of him!” cried Lestrade. He darted into the hall, and a few moments later his bullying voice sounded from the back room.

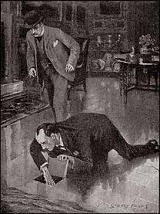

“Now, Watson, now!” cried Holmes with frenzied eagerness. All the demoniacal force of the man masked behind that listless manner burst out in a paroxysm of energy. He tore the drugget from the floor, and in an instant was down on his hands and knees clawing at each of the squares of wood beneath it. One turned sideways as he dug his nails into the edge of it. It hinged back like the lid of a box. A small black cavity opened beneath it. Holmes plunged his eager hand into it and drew it out with a bitter snarl of anger and disappointment. It was empty.

“Quick, Watson, quick! Get it back again!” The wooden lid was replaced, and the drugget had only just been drawn straight when Lestrade’s voice was heard in the passage. He found Holmes leaning languidly against the mantelpiece, resigned and patient, endeavouring to conceal his irrepressible yawns.

“Sorry to keep you waiting, Mr. Holmes. I can see that you are bored to death with the whole affair. Well, he has confessed, all right. Come in here, MacPherson. Let these gentlemen hear of your most inexcusable conduct.”

The big constable, very hot and penitent, sidled into the room.

“I meant no harm, sir, I’m sure. The young woman came to the door last evening - mistook the house, she did. And then we got talking. It’s lonesome, when you’re on duty here all day.”

“Well, what happened then?”

“She wanted to see where the crime was done - had read about it in the papers, she said. She was a very respectable, well-spoken young woman, sir, and I saw no harm in letting her have a peep. When she saw that mark on the carpet, down she dropped on the floor, and lay as if she were dead. I ran to the back and got some water, but I could not bring her to. Then I went round the corner to the Ivy Plant for some brandy, and by the time I had brought it back the young woman had recovered and was off - ashamed of herself, I daresay, and dared not face me.”

“How about moving that drugget?”

“Well, sir, it was a bit rumpled, certainly, when I came back. You see, she fell on it and it lies on a polished floor with nothing to keep it in place. I straightened it out afterwards.”