“Well, I found my plans very seriously menaced. It looked as if the pair might take an immediate departure, and so necessitate very prompt and energetic measures on my part. At the church door, however, they separated, he driving back to the temple, and she to her own house. ‘I shall drive out in the park at five as usual,’ she said as she left him. I heard no more. They drove away in different directions, and I went off to make my own arrangements.”

“Which are?”

“Some cold beef and a glass of beer,” he answered, ringing the bell. “I have been too busy to think of food, and I am likely to be busier still this evening. By the way, Doctor, I shall want your cooperation.”

“I shall be delighted.”

“You don’t mind breaking the law?”

“Not in the least.”

“Nor running a chance of arrest?”

“Not in a good cause.”

“Oh, the cause is excellent!”

“Then I am your man.”

“I was sure that I might rely on you.”

“But what is it you wish?”

“When Mrs. Turner has brought in the tray. I will make it clear to you. Now,” he said as he turned hungrily on the simple fare that our landlady had provided, “I must discuss it while I eat, for I have not much time. It is nearly five now. In two hours we must be on the scene of action. Miss Irene, or Madame, rather, returns from her drive at seven. We must be at Briony Lodge to meet her.”

“And what then?”

“You must leave that to me. I have already arranged what is to occur. There is only one point on which I must insist. You must not interfere, come what may. You understand?”

“I am to be neutral?”

“To do nothing whatever. There will probably be some small unpleasantness. Do not join in it. It will end in my being conveyed into the house. Four or five minutes afterwards the sitting-room window will open. You are to station yourself close to that open window.”

“Yes.”

“You are to watch me, for I will be visible to you.”

“Yes.”

“And when I raise my hand- so- you will throw into the room what I give you to throw, and will, at the same time, raise the cry of fire. You quite follow me?”

“Entirely.”

“It is nothing very formidable,” he said, taking a long cigar-shaped roll from his pocket. “It is an ordinary plumber’s smoke-rocket, fitted with a cap at either end to make it self-lighting. Your task is confined to that. When you raise your cry of fire, it will be taken up by quite a number of people. You may then walk to the end of the street, and I will rejoin you in ten minutes. I hope that I have made myself clear?”

“I am to remain neutral, to get near the window, to watch you, and at the signal to throw in this object, then to raise the cry of fire, and to wait you at the corner of the street.”

“Precisely.”

“Then you may entirely rely on me.”

“That is excellent. I think, perhaps, it is almost time that I prepare for the new role I have to play.”

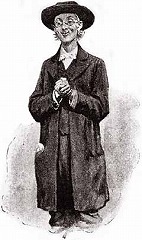

He disappeared into his bedroom and returned in a few minutes in the character of an amiable and simple-minded Nonconformist clergyman. His broad black hat, his baggy trousers, his white tie, his sympathetic smile, and general look of peering and benevolent curiosity were such as Mr. John Hare alone could have equalled. It was not merely that Holmes changed his costume. His expression, his manner, his very soul seemed to vary with every fresh part that he assumed. The stage lost a fine actor, even as science lost an acute reasoner, when he became a specialist in crime.