“It’s perfectly absurd, Mr. Holmes,” he said. “What can this man possibly know of what has occurred? It is waste of time and money.”

“He would not have telegraphed to you if he did not know something. Wire at once that you are coming.”

“I don’t think I shall go.”

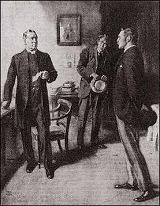

Holmes assumed his sternest aspect.

“It would make the worst possible impression both on the police and upon myself, Mr. Amberley, if when so obvious a clue arose you should refuse to follow it up. We should feel that you were not really in earnest in this investigation.”

Our client seemed horrified at the suggestion.

“Why, of course I shall go if you look at it in that way,” said he. “On the face of it, it seems absurd to suppose that this parson knows anything, but if you think- -”

“I do think,” said Holmes with emphasis, and so we were launched upon our journey. Holmes took me aside before we left the room and gave me one word of counsel, which showed that he considered the matter to be of importance. “Whatever you do, see that he really does go,” said he. “Should he break away or return, get to the nearest telephone exchange and send the single word ‘Bolted.’ I will arrange here that it shall reach me wherever I am.”

Little Purlington is not an easy place to reach, for it is on a branch line. My remembrance of the journey is not a pleasant one, for the weather was hot, the train slow, and my companion sullen and silent, hardly talking at all save to make an occasional sardonic remark as to the futility of our proceedings. When we at last reached the little station it was a two-mile drive before we came to the Vicarage, where a big, solemn, rather pompous clergyman received us in his study. Our telegram lay before him.

“Well, gentlemen,” he asked, “what can I do for you?”

“We came,” I explained, “in answer to your wire.”

“My wire! I sent no wire.”

“I mean the wire which you sent to Mr. Josiah Amberley about his wife and his money.”

“If this is a joke, sir, it is a very questionable one,” said the vicar angrily. “I have never heard of the gentleman you name, and I have not sent a wire to anyone.”

Our client and I looked at each other in amazement.

“Perhaps there is some mistake,” said I; “are there perhaps two vicarages? Here is the wire itself, signed Elman and dated from the Vicarage.”

“There is only one vicarage, sir, and only one vicar, and this wire is a scandalous forgery, the origin of which shall certainly be investigated by the police. Meanwhile, I can see no possible object in prolonging this interview.”

So Mr. Amberley and I found ourselves on the roadside in what seemed to me to be the most primitive village in England. We made for the telegraph office, but it was already closed. There was a telephone, however, at the little Railway Arms, and by it I got into touch with Holmes, who shared in our amazement at the result of our journey.

“Most singular!” said the distant voice. “Most remarkable! I much fear, my dear Watson, that there is no return train to-night. I have unwittingly condemned you to the horrors of a country inn. However, there is always Nature, Watson - Nature and Josiah Amberley - you can be in close commune with both.” I heard his dry chuckle as he turned away.

It was soon apparent to me that my companion’s reputation as a miser was not undeserved. He had grumbled at the expense of the journey, had insisted upon travelling third-class, and was now clamorous in his objections to the hotel bill. Next morning, when we did at last arrive in London, it was hard to say which of us was in the worse humour.

“You had best take Baker Street as we pass,” said I. “Mr. Holmes may have some fresh instructions.”