“They were certainly very much larger than any which he could have made, and were evidently quite fresh. It rained hard this afternoon, as you know, and my patients were the only people who called. It must have been the case, then, that the man in the waiting-room had, for some unknown reason, while I was busy with the other, ascended to the room of my resident patient. Nothing had been touched or taken, but there were the footprints to prove that the intrusion was an undoubted fact.

“Mr. Blessington seemed more excited over the matter than I should have thought possible, though of course it was enough to disturb anybody’s peace of mind. He actually sat crying in an armchair, and I could hardly get him to speak coherently. It was his suggestion that I should come round to you, and of course I at once saw the propriety of it, for certainly the incident is a very singular one, though he appears to completely overrate its importance. If you would only come back with me in my brougham, you would at least be able to soothe him, though I can hardly hope that you will be able to explain this remarkable occurrence.”

Sherlock Holmes had listened to this long narrative with an intentness which showed me that his interest was keenly aroused. His face was as impassive as ever, but his lids had drooped more heavily over his eyes, and his smoke had curled up more thickly from his pipe to emphasize each curious episode in the doctor’s tale. As our visitor concluded, Holmes sprang up without a word, handed me my hat, picked his own from the table, and followed Dr. Trevelyan to the door. Within a quarter of an hour we had been dropped at the door of the physician’s residence in Brook Street, one of those sombre, flat-faced houses which one associates with a West End practice. A small page admitted us, and we began at once to ascend the broad, well-carpeted stair.

But a singular interruption brought us to a standstill. The light at the top was suddenly whisked out, and from the darkness came a reedy, quavering voice.

“I have a pistol,” it cried. “I give you my word that I’ll fire if you come any nearer.”

“This really grows outrageous, Mr. Blessington,” cried Dr. Trevelyan.

“Oh, then it is you, Doctor,” said the voice with a great heave of relief. “But those other gentlemen, are they what they pretend to be?”

We were conscious of a long scrutiny out of the darkness.

“Yes, yes, it’s all right,” said the voice at last. “You can come up, and I am sorry if my precautions have annoyed you.”

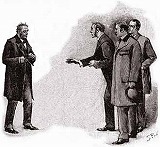

He relit the stair gas as he spoke, and we saw before us a singular-looking man, whose appearance, as well as his voice, testified to his jangled nerves. He was very fat, but had apparently at some time been much fatter, so that the skin hung about his face in loose pouches, like the cheeks of a bloodhound. He was of a sickly colour, and his thin, sandy hair seemed to bristle up with the intensity of his emotion. In his hand he held a pistol, but he thrust it into his pocket as we advanced.

“Good-evening, Mr. Holmes,” said he. “I am sure I am very much obliged to you for coming round. No one ever needed your advice more than I do. I suppose that Dr. Trevelyan has told you of this most unwarrantable intrusion into my rooms.”

“Quite so,” said Holmes. “Who are these two men, Mr. Blessington, and why do they wish to molest you?”

“Well, well,” said the resident patient in a nervous fashion, “of course it is hard to say that. You can hardly expect me to answer that, Mr. Holmes.”

“Do you mean that you don’t know?”

“Come in here, if you please. Just have the kindness to step in here.”

He led the way into his bedroom, which was large and comfortably furnished.