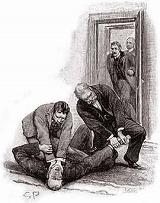

His words were cut short by a sudden scream of “Help! Help! Murder!” With a thrill I recognized the voice as that of my friend. I rushed madly from the room on to the landing. The cries, which had sunk down into a hoarse, inarticulate shouting, came from the room which we had first visited. I dashed in, and on into the dressing-room beyond. The two Cunninghams were bending over the prostrate figure of Sherlock Holmes, the younger clutching his throat with both hands, while the elder seemed to be twisting one of his wrists. In an instant the three of us had torn them away from him, and Holmes staggered to his feet, very pale and evidently greatly exhausted.

“Arrest these men, Inspector,” he gasped.

“On what charge?”

“That of murdering their coachman, William Kirwan.”

The inspector stared about him in bewilderment. “Oh, come now, Mr. Holmes,” said he at last, “I’m sure you don’t really mean to- -”

“Tut, man, look at their faces!” cried Holmes curtly.

Never certainly have I seen a plainer confession of guilt upon human countenances. The older man seemed numbed and dazed, with a heavy, sullen expression upon his strongly marked face. The son, on the other hand, had dropped all that jaunty, dashing style which had characterized him, and the ferocity of a dangerous wild beast gleamed in his dark eyes and distorted his handsome features. The inspector said nothing, but, stepping to the door, he blew his whistle. Two of his constables came at the call.

“I have no alternative, Mr. Cunningham,” said he. “I trust that this may all prove to be an absurd mistake, but you can see that- - Ah, would you? Drop it!” He struck out with his hand, and a revolver which the younger man was in the act of cocking clattered down upon the floor.

“Keep that,” said Holmes, quietly putting his foot upon it; “you will find it useful at the trial. But this is what we really wanted.” He held up a little crumpled piece of paper.

“The remainder of the sheet!” cried the inspector.

“Precisely.”

“And where was it?”

“Where I was sure it must be. I’ll make the whole matter clear to you presently. I think, Colonel, that you and Watson might return now, and I will be with you again in an hour at the furthest. The inspector and I must have a word with the prisoners, but you will certainly see me back at luncheon time.”

Sherlock Holmes was as good as his word, for about one o’clock he rejoined us in the colonel’s smoking-room. He was accompanied by a little elderly gentleman, who was introduced to me as the Mr. Acton whose house had been the scene of the original burglary.

“I wished Mr. Acton to be present while I demonstrated this small matter to you,” said Holmes, “for it is natural that he should take a keen interest in the details. I am afraid, my dear Colonel, that you must regret the hour that you took in such a stormy petrel as I am.”

“On the contrary,” answered the colonel warmly, “I consider it the greatest privilege to have been permitted to study your methods of working. I confess that they quite surpass my expectations, and that I am utterly unable to account for your result. I have not yet seen the vestige of a clue.”

“I am afraid that my explanation may disillusion you, but it has always been my habit to hide none of my methods, either from my friend Watson or from anyone who might take an intelligent interest in them. But, first, as I am rather shaken by the knocking about which I had in the dressing-room, I think that I shall help myself to a dash of your brandy, Colonel. My strength has been rather tried of late.”

“I trust you had no more of those nervous attacks.”