“How’s this, Watson?” he cried, picking up the paper from the table. “ ‘High red house with white stone facings. Third floor. Second window left. After dusk. G.’ That is definite enough. I think after breakfast we must make a little reconnaissance of Mrs. Warren’s neighbourhood. Ah, Mrs. Warren! what news do you bring us this morning?”

Our client had suddenly burst into the room with an explosive energy which told of some new and momentous development.

“It’s a police matter, Mr. Holmes!” she cried. “I’ll have no more of it! He shall pack out of there with his baggage. I would have gone straight up and told him so, only I thought it was but fair to you to take your opinion first. But I’m at the end of my patience, and when it comes to knocking my old man about- -”

“Knocking Mr. Warren about?”

“Using him roughly, anyway.”

“But who used him roughly?”

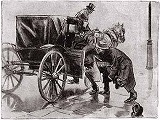

“Ah! that’s what we want to know! It was this morning, sir. Mr. Warren is a timekeeper at Morton and Waylight’s, in Tottenham Court Road. He has to be out of the house before seven. Well, this morning he had not gone ten paces down the road when two men came up behind him, threw a coat over his head, and bundled him into a cab that was beside the curb. They drove him an hour, and then opened the door and shot him out. He lay in the roadway so shaken in his wits that he never saw what became of the cab. When he picked himself up he found he was on Hampstead Heath; so he took a bus home, and there he lies now on the sofa, while I came straight round to tell you what had happened.”

“Most interesting,” said Holmes. “Did he observe the appearance of these men - did he hear them talk?”

“No; he is clean dazed. He just knows that he was lifted up as if by magic and dropped as if by magic. Two at least were in it, and maybe three.”

“And you connect this attack with your lodger?”

“Well, we’ve lived there fifteen years and no such happenings ever came before. I’ve had enough of him. Money’s not everything. I’ll have him out of my house before the day is done.”

“Wait a bit, Mrs. Warren. Do nothing rash. I begin to think that this affair may be very much more important than appeared at first sight. It is clear now that some danger is threatening your lodger. It is equally clear that his enemies, lying in wait for him near your door, mistook your husband for him in the foggy morning light. On discovering their mistake they released him. What they would have done had it not been a mistake, we can only conjecture.”

“Well, what am I to do, Mr. Holmes?”

“I have a great fancy to see this lodger of yours, Mrs. Warren.”

“I don’t see how that is to be managed, unless you break in the door. I always hear him unlock it as I go down the stair after I leave the tray.”

“He has to take the tray in. Surely we could conceal ourselves and see him do it.”

The landlady thought for a moment.

“Well, sir, there’s the box-room opposite. I could arrange a looking-glass, maybe, and if you were behind the door- -”

“Excellent!” said Holmes. “When does he lunch?”

“About one, sir.”

“Then Dr. Watson and I will come round in time. For the present, Mrs. Warren, good-bye.”

At half-past twelve we found ourselves upon the steps of Mrs. Warren’s house - a high, thin, yellow-brick edifice in Great Orme Street, a narrow thoroughfare at the northeast side of the British Museum. Standing as it does near the corner of the street, it commands a view down Howe Street, with its more pretentious houses. Holmes pointed with a chuckle to one of these, a row of residential flats, which projected so that they could not fail to catch the eye.