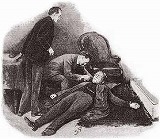

WE HAVE had some dramatic entrances and exits upon our small stage at Baker Street, but I cannot recollect anything more sudden and startling than the first appearance of Thorneycroft Huxtable, M.A., Ph.D., etc. His card, which seemed too small to carry the weight of his academic distinctions, preceded him by a few seconds, and then he entered himself - so large, so pompous, and so dignified that he was the very embodiment of self-possession and solidity. And yet his first action, when the door had closed behind him, was to stagger against the table, whence he slipped down upon the floor, and there was that majestic figure prostrate and insensible upon our bearskin hearthrug.

We had sprung to our feet, and for a few moments we stared in silent amazement at this ponderous piece of wreckage, which told of some sudden and fatal storm far out on the ocean of life. Then Holmes hurried with a cushion for his head, and I with brandy for his lips. The heavy, white face was seamed with lines of trouble, the hanging pouches under the closed eyes were leaden in colour, the loose mouth drooped dolorously at the corners, the rolling chins were unshaven. Collar and shirt bore the grime of a long journey, and the hair bristled unkempt from the well-shaped head. It was a sorely stricken man who lay before us.

“What is it, Watson?” asked Holmes.

“Absolute exhaustion - possibly mere hunger and fatigue,” said I, with my finger on the thready pulse, where the stream of life trickled thin and small.

“Return ticket from Mackleton, in the north of England,” said Holmes, drawing it from the watch-pocket. “It is not twelve o’clock yet. He has certainly been an early starter.”

The puckered eyelids had begun to quiver, and now a pair of vacant gray eyes looked up at us. An instant later the man had scrambled on to his feet, his face crimson with shame.

“Forgive this weakness, Mr. Holmes, I have been a little overwrought. Thank you, if I might have a glass of milk and a biscuit, I have no doubt that I should be better. I came personally, Mr. Holmes, in order to insure that you would return with me. I feared that no telegram would convince you of the absolute urgency of the case.”

“When you are quite restored- -”

“I am quite well again. I cannot imagine how I came to be so weak. I wish you, Mr. Holmes, to come to Mackleton with me by the next train.”

My friend shook his head.

“My colleague, Dr. Watson, could tell you that we are very busy at present. I am retained in this case of the Ferrers Documents, and the Abergavenny murder is coming up for trial. Only a very important issue could call me from London at present.”

“Important!” Our visitor threw up his hands. “Have you heard nothing of the abduction of the only son of the Duke of Holdernesse?”

“What! the late Cabinet Minister?”

“Exactly. We had tried to keep it out of the papers, but there was some rumor in the Globe last night. I thought it might have reached your ears.”

Holmes shot out his long, thin arm and picked out Volume “H” in his encyclopaedia of reference.

“ ‘Holdernesse, 6th Duke, K.G., P.C.’ - half the alphabet! ‘Baron Beverley, Earl of Carston’ - dear me, what a list! ‘Lord Lieutenant of Hallamshire since 1900. Married Edith, daughter of Sir Charles Appledore, 1888. Heir and only child, Lord Saltire. Owns about two hundred and fifty thousand acres. Minerals in Lancashire and Wales. Address: Carlton House Terrace; Holdernesse Hall, Hallamshire; Carston Castle, Bangor, Wales. Lord of the Admiralty, 1872; Chief Secretary of State for- -’ Well, well, this man is certainly one of the greatest subjects of the Crown!”