And my words were true, for shortly after eight a hansom dashed up to the door and our friend got out of it. Standing in the window we saw that his left hand was swathed in a bandage and that his face was very grim and pale. He entered the house, but it was some little time before he came upstairs.

“He looks like a beaten man,” cried Phelps.

I was forced to confess that he was right. “After all,” said I, “the clue of the matter lies probably here in town.”

Phelps gave a groan.

“I don’t know how it is,” said he, “but I had hoped for so much from his return. But surely his hand was not tied up like that yesterday. What can be the matter?”

“You are not wounded, Holmes?” I asked as my friend entered the room.

“Tut, it is only a scratch through my own clumsiness,” he answered, nodding his good-morning to us. “This case of yours, Mr. Phelps, is certainly one of the darkest which I have ever investigated.”

“I feared that you would find it beyond you.”

“It has been a most remarkable experience.”

“That bandage tells of adventures,” said I. “Won’t you tell us what has happened?”

“After breakfast, my dear Watson. Remember that I have breathed thirty miles of Surrey air this morning. I suppose that there has been no answer from my cabman advertisement? Well, well, we cannot expect to score every time.”

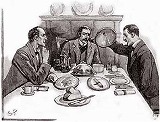

The table was all laid, and just as I was about to ring Mrs. Hudson entered with the tea and coffee. A few minutes later she brought in three covers, and we all drew up to the table, Holmes ravenous, I curious, and Phelps in the gloomiest state of depression.

“Mrs. Hudson has risen to the occasion,” said Holmes, uncovering a dish of curried chicken. “Her cuisine is a little limited, but she has as good an idea of breakfast as a Scotchwoman. What have you there, Watson?”

“Ham and eggs,” I answered.

“Good! What are you going to take, Mr. Phelps - curried fowl or eggs, or will you help yourself?”

“Thank you. I can eat nothing,” said Phelps.

“Oh, come! Try the dish before you.”

“Thank you, I would really rather not.”

“Well, then,” said Holmes with a mischievous twinkle, “I suppose that you have no objection to helping me?”

Phelps raised the cover, and as he did so he uttered a scream and sat there staring with a face as white as the plate upon which he looked. Across the centre of it was lying a little cylinder of blue-gray paper. He caught it up, devoured it with his eyes, and then danced madly about the room, pressing it to his bosom and shrieking out in his delight. Then he fell back into an armchair, so limp and exhausted with his own emotions that we had to pour brandy down his throat to keep him from fainting.

“There! there!” said Holmes soothingly, patting him upon the shoulder. “It was too bad to spring it on you like this, but Watson here will tell you that I never can resist a touch of the dramatic.”

Phelps seized his hand and kissed it. “God bless you!” he cried. “You have saved my honour.”

“Well, my own was at stake, you know,” said Holmes. “I assure you it is just as hateful to me to fail in a case as it can be to you to blunder over a commission.”

Phelps thrust away the precious document into the innermost pocket of his coat.

“I have not the heart to interrupt your breakfast any further, and yet I am dying to know how you got it and where it was.”

Sherlock Holmes swallowed a cup of coffee and turned his attention to the ham and eggs. Then he rose, lit his pipe, and settled himself down into his chair.