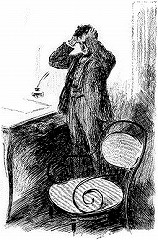

“A cold hand seemed to close round my heart. Someone, then, was in that room where my precious treaty lay upon the table. I ran frantically up the stair and along the passage. There was no one in the corridors, Mr. Holmes. There was no one in the room. All was exactly as I left it, save only that the papers which had been committed to my care had been taken from the desk on which they lay. The copy was there, and the original was gone.”

Holmes sat up in his chair and rubbed his hands. I could see that the problem was entirely to his heart. “Pray, what did you do then?” he murmured.

“I recognized in an instant that the thief must have come up the stairs from the side door. Of course I must have met him if he had come the other way.”

“You were satisfied that he could not have been concealed , in the room all the timeor in the corridor which you have just described as dimly lighted?”

“It is absolutely impossible. A rat could not conceal himself either in the room or the corridor. There is no cover at all.”

“Thank you. Pray proceed.”

“The commissionaire, seeing by my pale face that something was to be feared, had followed me upstairs. Now we both rushed along the corridor and down the steep steps which led to Charles Street. The door at the bottom was closed but unlocked. We flung it open and rushed out. I can distinctly remember that as we did so there came three chimes from a neighbouring clock. It was a quarter to ten.”

“That is of enormous importance,” said Holmes, making a note upon his shirt-cuff.

“The night was very dark, and a thin, warm rain was falling. There was no one in Charles Street, but a great traffic was going on, as usual,in Whitehall, at the extremity. We rushed along the pavement, bare-headed as we were, and at the far corner we found a policeman standing.

“ ‘A robbery has been committed,’ I gasped. ‘A document of immense value has been stolen from the Foreign Office. Has anyone passed this way?’

“ ‘I have been standing here for a quarter of an hour, sir,’ said he, ‘only one person has passed during that time -a woman, tall and elderly, with a Paisley shawl.’

“ ‘Ah, that is only my wife,’ cried the commissionaire; ‘has no one else passed?’

“ ‘No one.’

“ ‘Then it must be the other way that the thief took,’ cried the fellow, tugging at my sleeve.

“But I was not satisfied, and the attempts which he made to draw me away increased my suspicions.

“ ‘Which way did the woman go?’ I cried.

“ ‘I don’t know, sir. I noticed her pass, but I had no special reason for watching her. She seemed to be in a hurry.’

“ ‘How long ago was it?’

“ ‘Oh, not very many minutes.’

“ ‘Within the last five?’

“ ‘Well, it could not be more than five.’

“ ‘You’re only wasting your time, sir, and every minute now is of importance,’ cried the commissionaire; ‘take my word for it that my old woman has nothing to do with it and come down to the other end of the street. Well, if you won’t, I will.’ And with that he rushed off in the other direction.

“But I was after him in an instant and caught him by the sleeve.

“ ‘Where do you live?’ said I.

“ ‘16 Ivy Lane, Brixton,’ he answered. ‘But don’t let yourself be drawn away upon a false scent, Mr. Phelps. Come to the other end of the street and let us see if we can hear of anything.’

“Nothing was to be lost by following his advice. With the policeman we both hurried down, but only to find the street full of traffic, many people coming and going, but all only too eager to get to a place of safety upon so wet a night. There was no lounger who could tell us who had passed.