There was something that touched me as I read this letter, something pitiable in the reiterated appeals to bring Holmes. So moved was I that even had it been a difficult matter I should have tried it, but of course I knew well that Holmes loved his art, so that he was ever as ready to bring his aid as his client could be to receive it. My wife agreed with me that not a moment should be lost in laying the matter before him, and so within an hour of breakfast-time I found myself back once more in the old rooms in Baker Street.

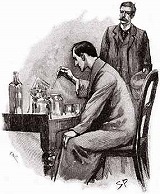

Holmes was seated at his side-table clad in his dressing-gown and working hard over a chemical investigation. A large curved retort was boiling furiously in the bluish flame of a Bunsen burner, and the distilled drops were condensing into a two-litre measure. My friend hardly glanced up as I entered, and I, seeing that his investigation must be of importance, seated myself in an armchair and waited. He dipped into this bottle or that, drawing out a few drops of each with his glass pipette, and finally brought a test-tube containing a solution over to the table. In his right hand he held a slip of litmus-paper.

“You come at a crisis, Watson,” said he. “If this paper remains blue, all is well. If it turns red, it means a man’s life.” He dipped it into the test-tube and it flushed at once into a dull, dirty crimson. “Hum! I thought as much!” he cried. “I will be at your service in an instant, Watson. You will find tobacco in the Persian slipper.” He turned to his desk and scribbled off several telegrams, which were handed over to the page-boy. Then he threw himself down into the chair opposite and drew up his knees until his fingers clasped round his long, thin shins.

“A very commonplace little murder,” said he. “You’ve got something better, I fancy. You are the stormy petrel of crime, Watson. What is it?”

I handed him the letter, which he read with the most concentrated attention.

“It does not tell us very much, does it?” he remarked as he handed it back to me.

“Hardly anything.”

“And yet the writing is of interest.”

“But the writing is not his own.”

“Precisely. It is a woman’s.”

“A man’s surely,” I cried.

“No, a woman’s, and a woman of rare character. You see, at the commencement of an investigation it is something to know that your client is in close contact with someone who, for good or evil, has an exceptional nature. My interest is already awakened in the case. If you are ready we will start at once for Woking and see this diplomatist who is in such evil case and the lady to whom he dictates his letters.”

We were fortunate enough to catch an early train at Waterloo, and in a little under an hour we found ourselves among the fir-woods and the heather of Woking. Briarbrae proved to be a large detached house standing in extensive grounds within a few minutes’ walk of the station. On sending in our cards we were shown into an elegantly appointed drawing-room, where we were joined in a few minutes by a rather stout man who received us with much hospitality. His age may have been nearer forty than thirty, but his cheeks were so ruddy and his eyes so merry that he still conveyed the impression of a plump and mischievous boy.

“I am so glad that you have come,” said he, shaking our hands with effusion. “Percy has been inquiring for you all morning. Ah, poor old chap, he clings to any straw! His father and his mother asked me to see you, for the mere mention of the subject is very painful to them.”

“We have had no details yet,” observed Holmes. “I perceive that you are not yourself a member of the family.”

Our acquaintance looked surprised, and then, glancing down, he began to laugh.