“It is certainly a little untrustworthy,” said Holmes. “It will require some checking and you have little time to check it. Your admiral may find the new guns rather larger than he expects, and the cruisers perhaps a trifle faster.”

Von Bork clutched at his own throat in despair.

“There are a good many other points of detail which will, no doubt, come to light in good time. But you have one quality which is very rare in a German, Mr. Von Bork: you are a sportsman and you will bear me no ill-will when you realize that you, who have outwitted so many other people, have at last been outwitted yourself. After all, you have done your best for your country, and I have done my best for mine, and what could be more natural? Besides,” he added, not unkindly, as he laid his hand upon the shoulder of the prostrate man, “it is better than to fall before some more ignoble foe. These papers are now ready, Watson. If you will help me with our prisoner, I think that we may get started for London at once.”

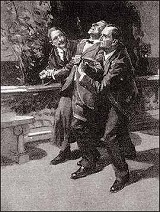

It was no easy task to move Von Bork, for he was a strong and a desperate man. Finally, holding either arm, the two friends walked him very slowly down the garden walk which he had trod with such proud confidence when he received the congratulations of the famous diplomatist only a few hours before. After a short, final struggle he was hoisted, still bound hand and foot, into the spare seat of the little car. His precious valise was wedged in beside him.

“I trust that you are as comfortable as circumstances permit,” said Holmes when the final arrangements were made. “Should I be guilty of a liberty if I lit a cigar and placed it between your lips?”

But all amenities were wasted upon the angry German.

“I suppose you realize, Mr. Sherlock Holmes,” said he, “that if your government bears you out in this treatment it becomes an act of war.”

“What about your government and all this treatment?” said Holmes, tapping the valise.

“You are a private individual. You have no warrant for my arrest. The whole proceeding is absolutely illegal and outrageous.”

“Absolutely,” said Holmes.

“Kidnapping a German subject.”

“And stealing his private papers.”

“Well, you realize your position, you and your accomplice here. If I were to shout for help as we pass through the village- -”

“My dear sir, if you did anything so foolish you would probably enlarge the too limited titles of our village inns by giving us ‘The Dangling Prussian’ as a signpost. The Englishman is a patient creature, but at present his temper is a little inflamed, and it would be as well not to try him too far. No, Mr. Von Bork, you will go with us in a quiet, sensible fashion to Scotland Yard, whence you can send for your friend, Baron Von Herling, and see if even now you may not fill that place which he has reserved for you in the ambassadorial suite. As to you, Watson, you are joining us with your old service, as I understand, so London won’t be out of your way. Stand with me here upon the terrace, for it may be the last quiet talk that we shall ever have.”

The two friends chatted in intimate converse for a few minutes, recalling once again the days of the past, while their prisoner vainly wriggled to undo the bonds that held him. As they turned to the car Holmes pointed back to the moonlit sea and shook a thoughtful head.

“There’s an east wind coming, Watson.”

“I think not, Holmes. It is very warm.”