“He has begun to pawn the jewels. We should get him now.”

“But does this mean that any harm has befallen the Lady Frances?”

Holmes shook his head very gravely.

“Supposing that they have held her prisoner up to now, it is clear that they cannot let her loose without their own destruction. We must prepare for the worst.”

“What can I do?”

“These people do not know you by sight?”

“No.”

“It is possible that he will go to some other pawnbroker in the future. In that case, we must begin again. On the other hand, he has had a fair price and no questions asked, so if he is in need of ready-money he will probably come back to Bovington’s. I will give you a note to them, and they will let you wait in the shop. If the fellow comes you will follow him home. But no indiscretion, and, above all, no violence. I put you on your honour that you will take no step without my knowledge and consent.”

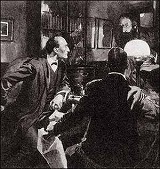

For two days the Hon. Philip Green (he was, I may mention, the son of the famous admiral of that name who commanded the Sea of Azof fleet in the Crimean War) brought us no news. On the evening of the third he rushed into our sitting-room, pale, trembling, with every muscle of his powerful frame quivering with excitement.

“We have him! We have him!” he cried.

He was incoherent in his agitation. Holmes soothed him with a few words and thrust him into an armchair.

“Come, now, give us the order of events,” said he.

“She came only an hour ago. It was the wife, this time, but the pendant she brought was the fellow of the other. She is a tall, pale woman, with ferret eyes.”

“That is the lady,” said Holmes.

“She left the office and I followed her. She walked up the Kennington Road, and I kept behind her. Presently she went into a shop. Mr. Holmes, it was an undertaker’s.”

My companion started. “Well?” he asked in that vibrant voice which told of the fiery soul behind the cold gray face.

“She was talking to the woman behind the counter. I entered as well. ‘It is late,’ I heard her say, or words to that effect. The woman was excusing herself. ‘It should be there before now,’ she answered. ‘It took longer, being out of the ordinary.’ They both stopped and looked at me, so I asked some question and then left the shop.”

“You did excellently well. What happened next?”

“The woman came out, but I had hid myself in a doorway. Her suspicions had been aroused, I think, for she looked round her. Then she called a cab and got in. I was lucky enough to get another and so to follow her. She got down at last at No. 36, Poultney Square, Brixton. I drove past, left my cab at the corner of the square, and watched the house.”

“Did you see anyone?”

“The windows were all in darkness save one on the lower floor. The blind was down, and I could not see in. I was standing there, wondering what I should do next, when a covered van drove up with two men in it. They descended, took something out of the van, and carried it up the steps to the hall door. Mr. Holmes, it was a coffin.”

“Ah!”

“For an instant I was on the point of rushing in. The door had been opened to admit the men and their burden. It was the woman who had opened it. But as I stood there she caught a glimpse of me, and I think that she recognized me. I saw her start, and she hastily closed the door. I remembered my promise to you, and here I am.”