Sir Henry was more pleased than surprised to see Sherlock Holmes, for he had for some days been expecting that recent events would bring him down from London. He did raise his eyebrows, however, when he found that my friend had neither any luggage nor any explanations for its absence. Between us we soon supplied his wants, and then over a belated supper we explained to the baronet as much of our experience as it seemed desirable that he should know. But first I had the unpleasant duty of breaking the news to Barrymore and his wife. To him it may have been an unmitigated relief, but she wept bitterly in her apron. To all the world he was the man of violence, half animal and half demon; but to her he always remained the little wilful boy of her own girlhood, the child who had clung to her hand. Evil indeed is the man who has not one woman to mourn him.

“I’ve been moping in the house all day since Watson went off in the morning,” said the baronet. “I guess I should have some credit, for I have kept my promise. If I hadn’t sworn not to go about alone I might have had a more lively evening, for I had a message from Stapleton asking me over there.”

“I have no doubt that you would have had a more lively evening,” said Holmes drily. “By the way, I don’t suppose you appreciate that we have been mourning over you as having broken your neck?”

Sir Henry opened his eyes. “How was that?”

“This poor wretch was dressed in your clothes. I fear your servant who gave them to him may get into trouble with the police.”

“That is unlikely. There was no mark on any of them, as far as I know.”

“That’s lucky for him - in fact, it’s lucky for all of you, since you are all on the wrong side of the law in this matter. I am not sure that as a conscientious detective my first duty is not to arrest the whole household. Watson’s reports are most incriminating documents.”

“But how about the case?” asked the baronet. “Have you made anything out of the tangle? I don’t know that Watson and I are much the wiser since we came down.”

“I think that I shall be in a position to make the situation rather more clear to you before long. It has been an exceedingly difficult and most complicated business. There are several points upon which we still want light - but it is coming all the same.”

“We’ve had one experience, as Watson has no doubt told you. We heard the hound on the moor, so I can swear that it is not all empty superstition. I had something to do with dogs when I was out West, and I know one when I hear one. If you can muzzle that one and put him on a chain I’ll be ready to swear you are the greatest detective of all time.”

“I think I will muzzle him and chain him all right if you will give me your help.”

“Whatever you tell me to do I will do.”

“Very good; and I will ask you also to do it blindly, without always asking the reason.”

“Just as you like.”

“If you will do this I think the chances are that our little problem will soon be solved. I have no doubt- -”

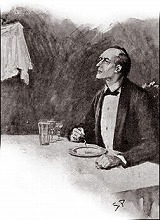

He stopped suddenly and stared fixedly up over my head into the air. The lamp beat upon his face, and so intent was it and so still that it might have been that of a clear-cut classical statue, a personification of alertness and expectation.

“What is it?” we both cried.

I could see as he looked down that he was repressing some internal emotion. His features were still composed, but his eyes shone with amused exultation.