“Well, then, why this hound should be loose to-night. I suppose that it does not always run loose upon the moor. Stapleton would not let it go unless he had reason to think that Sir Henry would be there.”

“My difficulty is the more formidable of the two, for I think that we shall very shortly get an explanation of yours, while mine may remain forever a mystery. The question now is, what shall we do with this poor wretch’s body? We cannot leave it here to the foxes and the ravens.”

“I suggest that we put it in one of the huts until we can communicate with the police.”

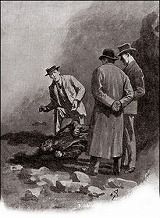

“Exactly. I have no doubt that you and I could carry it so far. Halloa, Watson, what’s this? It’s the man himself, by all that’s wonderful and audacious! Not a word to show your suspicions - not a word, or my plans crumble to the ground.”

A figure was approaching us over the moor, and I saw the dull red glow of a cigar. The moon shone upon him, and I could distinguish the dapper shape and jaunty walk of the naturalist. He stopped when he saw us, and then came on again.

“Why, Dr. Watson, that’s not you, is it? You are the last man that I should have expected to see out on the moor at this time of night. But, dear me, what’s this? Somebody hurt? Not - don’t tell me that it is our friend Sir Henry!” He hurried past me and stooped over the dead man. I heard a sharp intake of his breath and the cigar fell from his fingers.

“Who - who’s this?” he stammered.

“It is Selden, the man who escaped from Princetown.”

Stapleton turned a ghastly face upon us, but by a supreme effort he had overcome his amazement and his disappointment. He looked sharply from Holmes to me.

“Dear me! What a very shocking affair! How did he die?”

“He appears to have broken his neck by falling over these rocks. My friend and I were strolling on the moor when we heard a cry.”

“I heard a cry also. That was what brought me out. I was uneasy about Sir Henry.”

“Why about Sir Henry in particular?” I could not help asking.

“Because I had suggested that he should come over. When he did not come I was surprised, and I naturally became alarmed for his safety when I heard cries upon the moor. By the way” - his eyes darted again from my face to Holmes’s - “did you hear anything else besides a cry?”

“No,” said Holmes; “did you?”

“No.”

“What do you mean, then?”

“Oh, you know the stories that the peasants tell about a phantom hound, and so on. It is said to be heard at night upon the moor. I was wondering if there were any evidence of such a sound to-night.”

“We heard nothing of the kind,” said I.

“And what is your theory of this poor fellow’s death?”

“I have no doubt that anxiety and exposure have driven him off his head. He has rushed about the moor in a crazy state and eventually fallen over here and broken his neck.”

“That seems the most reasonable theory,” said Stapleton, and he gave a sigh which I took to indicate his relief. “What do you think about it, Mr. Sherlock Holmes?”

My friend bowed his compliments.

“You are quick at identification,” said he.

“We have been expecting you in these parts since Dr. Watson came down. You are in time to see a tragedy.”

“Yes, indeed. I have no doubt that my friend’s explanation will cover the facts. I will take an unpleasant remembrance back to London with me to-morrow.”

“Oh, you return to-morrow?”

“That is my intention.”

“I hope your visit has cast some light upon those occurrences which have puzzled us?”

Holmes shrugged his shoulders.