SHERLOCK HOLMES had, in a very remarkable degree, the power of detaching his mind at will. For two hours the strange business in which we had been involved appeared to be forgotten, and he was entirely absorbed in the pictures of the modern Belgian masters. He would talk of nothing but art, of which he had the crudest ideas, from our leaving the gallery until we found ourselves at the Northumberland Hotel.

“Sir Henry Baskerville is upstairs expecting you,” said the clerk. “He asked me to show you up at once when you came.”

“Have you any objection to my looking at your register?” said Holmes.

“Not in the least.”

The book showed that two names had been added after that of Baskerville. One was Theophilus Johnson and family, of Newcastle; the other Mrs. Oldmore and maid, of High Lodge, Alton.

“Surely that must be the same Johnson whom I used to know,” said Holmes to the porter. “A lawyer, is he not, gray-headed, and walks with a limp?”

“No, sir, this is Mr. Johnson, the coal-owner, a very active gentleman, not older than yourself.”

“Surely you are mistaken about his trade?”

“No, sir! he has used this hotel for many years, and he is very well known to us.”

“Ah, that settles it. Mrs. Oldmore, too; I seem to remember the name. Excuse my curiosity, but often in calling upon one friend one finds another.”

“She is an invalid lady, sir. Her husband was once mayor of Gloucester. She always comes to us when she is in town.”

“Thank you; I am afraid I cannot claim her acquaintance. We have established a most important fact by these questions, Watson,” he continued in a low voice as we went upstairs together. “We know now that the people who are so interested in our friend have not settled down in his own hotel. That means that while they are, as we have seen, very anxious to watch him, they are equally anxious that he should not see them. Now, this is a most suggestive fact.”

“What does it suggest?”

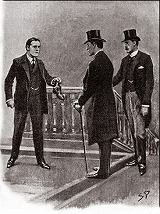

“It suggests - halloa, my dear fellow, what on earth is the matter?”

As we came round the top of the stairs we had run up against Sir Henry Baskerville himself. His face was flushed with anger, and he held an old and dusty boot in one of his hands. So furious was he that he was hardly articulate, and when he did speak it was in a much broader and more Western dialect than any which we had heard from him in the morning.

“Seems to me they are playing me for a sucker in this hotel,” he cried. “They’ll find they’ve started in to monkey with the wrong man unless they are careful. By thunder, if that chap can’t find my missing boot there will be trouble. I can take a joke with the best, Mr. Holmes, but they’ve got a bit over the mark this time.”

“Still looking for your boot?”

“Yes, sir, and mean to find it.”

“But, surely, you said that it was a new brown boot?”

“So it was, sir. And now it’s an old black one.”

“What! you don’t mean to say- -?”

“That’s just what I do mean to say. I only had three pairs in the world - the new brown, the old black, and the patent leathers, which I am wearing. Last night they took one of my brown ones, and to-day they have sneaked one of the black. Well, have you got it? Speak out, man, and don’t stand staring!”

An agitated German waiter had appeared upon the scene.

“No, sir; I have made inquiry all over the hotel, but I can hear no word of it.”

“Well, either that boot comes back before sundown or I’ll see the manager and tell him that I go right straight out of this hotel.”

“It shall be found, sir - I promise you that if you will have a little patience it will be found.”