“It has been pouring rain and blowing a hurricane ever since,” said he. “It will be harder to read now than that palimpsest. Well, well, it can’t be helped. What did you do, Hopkins, after you had made certain that you had made certain of nothing?”

“I think I made certain of a good deal, Mr. Holmes. I knew that someone had entered the house cautiously from without. I next examined the corridor. It is lined with cocoanut matting and had taken no impression of any kind. This brought me into the study itself. It is a scantily furnished room. The main article is a large writing-table with a fixed bureau. This bureau consists of a double column of drawers, with a central small cupboard between them. The drawers were open, the cupboard locked. The drawers, it seems, were always open, and nothing of value was kept in them. There were some papers of importance in the cupboard, but there were no signs that this had been tampered with, and the professor assures me that nothing was missing. It is certain that no robbery has been committed.

“I come now to the body of the young man. It was found near the bureau, and just to the left of it, as marked upon that chart. The stab was on the right side of the neck and from behind forward, so that it is almost impossible that it could have been self-inflicted.”

“Unless he fell upon the knife,” said Holmes.

“Exactly. The idea crossed my mind. But we found the knife some feet away from the body, so that seems impossible. Then, of course, there are the man’s own dying words. And, finally, there was this very important piece of evidence which was found clasped in the dead man’s right hand.”

From his pocket Stanley Hopkins drew a small paper packet. He unfolded it and disclosed a golden pince-nez, with two broken ends of black silk cord dangling from the end of it. “Willoughby Smith had excellent sight,” he added. “There can be no question that this was snatched from the face or the person of the assassin.”

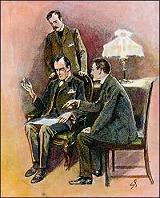

Sherlock Holmes took the glasses into his hand, and examined them with the utmost attention and interest. He held them on his nose, endeavoured to read through them, went to the window and stared up the street with them, looked at them most minutely in the full light of the lamp, and finally, with a chuckle, seated himself at the table and wrote a few lines upon a sheet of paper, which he tossed across to Stanley Hopkins.

“That’s the best I can do for you,” said he. “It may prove to be of some use.”

The astonished detective read the note aloud. It ran as follows:

“Wanted, a woman of good address, attired like a lady. She has a remarkably thick nose, with eyes which are set close upon either side of it. She has a puckered forehead, a peering expression, and probably rounded shoulders. There are indications that she has had recourse to an optician at least twice during the last few months. As her glasses are of remarkable strength, and as opticians are not very numerous, there should be no difficulty in tracing her.”

Holmes smiled at the astonishment of Hopkins, which must have been reflected upon my features.