“ ‘My father made the fellow gardener,’ said my companion, ‘and then, as that did not satisfy him, he was promoted to be butler. The house seemed to be at his mercy, and he wandered about and did what he chose in it. The maids complained of his drunken habits and his vile language. The dad raised their wages all round to recompense them for the annoyance. The fellow would take the boat and my father’s best gun and treat himself to little shooting trips. And all this with such a sneering, leering, insolent face that I would have knocked him down twenty times over if he had been a man of my own age. I tell you, Holmes, I have had to keep a tight hold upon myself all this time; and now I am asking myself whether, if I had let myself go a little more, I might not have been a wiser man.

“ ‘Well, matters went from bad to worse with us, and this animal Hudson became more and more intrusive, until at last, on his making some insolent reply to my father in my presence one day, I took him by the shoulders and turned him out of the room. He slunk away with a livid face and two venomous eyes which uttered more threats than his tongue could do. I don’t know what passed between the poor dad and him after that, but the dad came to me next day and asked me whether I would mind apologizing to Hudson. I refused, as you can imagine, and asked my father how he could allow such a wretch to take such liberties with himself and his household.

“ ‘ “Ah, my boy,” said he, “it is all very well to talk, but you don’t know how I am placed. But you shall know, Victor. I’ll see that you shall know, come what may. You wouldn’t believe harm of your poor old father, would you, lad?” He was very much moved and shut himself up in the study all day, where I could see through the window that he was writing busily.

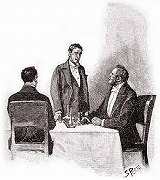

“ ‘That evening there came what seemed to me to be a grand release, for Hudson told us that he was going to leave us. He walked into the dining-room as we sat after dinner and announced his intention in the thick voice of a half-drunken man.

“ ‘ “I’ve had enough of Norfolk,” said he. “I’ll run down to Mr. Beddoes in Hampshire. He’ll be as glad to see me as you were, I daresay.”

“ ‘ “You’re not going away in an unkind spirit, Hudson, I hope,” said my father with a tameness which made my blood boil.

“ ‘ “I’ve not had my ’pology,” said he sulkily, glancing in my direction.

“ ‘ “Victor, you will acknowledge that you have used this worthy fellow rather roughly,” said the dad, turning to me.

“ ‘ “On the contrary, I think that we have both shown extraordinary patience towards him,” I answered.

“ ‘ “Oh, you do, do you?” he snarled. “Very good, mate. We’ll see about that!”

“ ‘He slouched out of the room and half an hour afterwards left the house, leaving my father in a state of pitiable nervousness. Night after night I heard him pacing his room, and it was just as he was recovering his confidence that the blow did at last fall.’

“ ‘And how?’ I asked eagerly.

“ ‘In a most extraordinary fashion. A letter arrived for my father yesterday evening, bearing the Fordingham postmark. My father read it, clapped both his hands to his head, and began running round the room in little circles like a man who has been driven out of his senses. When I at last drew him down on to the sofa, his mouth and eyelids were all puckered on one side, and I saw that he had a stroke. Dr. Fordham came over at once. We put him to bed, but the paralysis has spread, he has shown no sign of returning consciousness, and I think that we shall hardly find him alive.’

“ ‘You horrify me, Trevor!’ I cried. ‘What then could have been in this letter to cause so dreadful a result?’