“I hardly think that likely. I never saw a more inexorable face in my life.”

“Oh, we shall soon clear up all that,” said Bradstreet. “Well, I have drawn my circle, and I only wish I knew at what point upon it the folk that we are in search of are to be found.”

“I think I could lay my finger on it,” said Holmes quietly.

“Really, now!” cried the inspector, “you have formed your opinion! Come, now, we shall see who agrees with you. I say it is south, for the country is more deserted there.”

“And I say east,” said my patient.

“I am for west,” remarked the plain-clothes man. “There are several quiet little villages up there.”

“And I am for north,” said I, “because there are no hills there, and our friend says that he did not notice the carriage go up any.”

“Come,” cried the inspector, laughing; “it’s a very pretty diversity of opinion. We have boxed the compass among us. Who do you give your casting vote to?”

“You are all wrong.”

“But we can’t all be.”

“Oh, yes, you can. This is my point.” He placed his finger in the centre of the circle. “This is where we shall find them.”

“But the twelve-mile drive?” gasped Hatherley.

“Six out and six back. Nothing simpler. You say yourself that the horse was fresh and glossy when you got in. How could it be that if it had gone twelve miles over heavy roads?”

“Indeed, it is a likely ruse enough,” observed Bradstreet thoughtfully. “Of course there can be no doubt as to the nature of this gang.”

“None at all,” said Holmes. “They are coiners on a large scale, and have used the machine to form the amalgam which has taken the place of silver.”

“We have known for some time that a clever gang was at work,” said the inspector. “They have been turning out half-crowns by the thousand. We even traced them as far as Reading, but could get no farther, for they had covered their traces in a way that showed that they were very old hands. But now, thanks to this lucky chance, I think that we have got them right enough.”

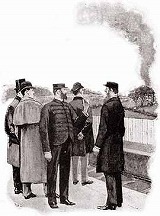

But the inspector was mistaken, for those criminals were not destined to fall into the hands of justice. As we rolled into Eyford Station we saw a gigantic column of smoke which streamed up from behind a small clump of trees in the neighbourhood and hung like an immense ostrich feather over the landscape.

“A house on fire?” asked Bradstreet as the train steamed off again on its way.

“Yes, sir!” said the station-master.

“When did it break out?”

“I hear that it was during the night, sir, but it has got worse, and the whole place is in a blaze.”

“Whose house is it?”

“Dr. Becher’s.”

“Tell me,” broke in the engineer, “is Dr. Becher a German, very thin, with a long, sharp nose?”

The station-master laughed heartily. “No, sir, Dr. Becher is an Englishman, and there isn’t a man in the parish who has a better-lined waistcoat. But he has a gentleman staying with him, a patient, as I understand, who is a foreigner, and he looks as if a little good Berkshire beef would do him no harm.”

The station-master had not finished his speech before we were all hastening in the direction of the fire. The road topped a low hill, and there was a great widespread whitewashed building in front of us, spouting fire at every chink and window, while in the garden in front three fire-engines were vainly striving to keep the flames under.

“That’s it!” cried Hatherley, in intense excitement. “There is the gravel-drive, and there are the rose-bushes where I lay. That second window is the one that I jumped from.”