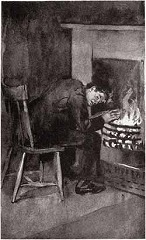

“Good, Simpson!” said Holmes, patting him on the head. “Come along, Watson. This is the house.” He sent in his card with a message that he had come on important business, and a moment later we were face to face with the man whom we had come to see. In spite of the warm weather he was crouching over a fire, and the little room was like an oven. The man sat all twisted and huddled in his chair in a way which gave an indescribable impression of deformity; but the face which he turned towards us, though worn and swarthy, must at some time have been remarkable for its beauty. He looked suspiciously at us now out of yellow-shot, bilious eyes, and, without speaking or rising, he waved towards two chairs.

“Mr. Henry Wood, late of India, I believe,” said Holmes affably. “I’ve come over this little matter of Colonel Barclay’s death.”

“What should I know about that?”

“That’s what I want to ascertain. You know, I suppose, that unless the matter is cleared up, Mrs. Barclay, who is an old friend of yours, will in all probability be tried for murder.”

The man gave a violent start.

“I don’t know who you are,” he cried, “nor how you come to know what you do know, but will you swear that this is true that you tell me?”

“Why, they are only waiting for her to come to her senses to arrest her.”

“My God! Are you in the police yourself?”

“No.”

“What business is it of yours, then?”

“It’s every man’s business to see justice done.”

“You can take my word that she is innocent.”

“Then you are guilty.”

“No, I am not.”

“Who killed Colonel James Barclay, then?”

“It was a just Providence that killed him. But, mind you this, that if I had knocked his brains out, as it was in my heart to do, he would have had no more than his due from my hands. If his own guilty conscience had not struck him down it is likely enough that I might have had his blood upon my soul. You want me to tell the story. Well, I don’t know why I shouldn’t, for there’s no cause for me to be ashamed of it.

“It was in this way, sir. You see me now with my back like a camel and my ribs all awry, but there was a time when Corporal Henry Wood was the smartest man in the One Hundred and Seventeenth foot. We were in India, then, in cantonments, at a place we’ll call Bhurtee. Barclay, who died the other day, was sergeant in the same company as myself, and the belle of the regiment, ay, and the finest girl that ever had the breath of life between her lips, was Nancy Devoy, the daughter of the colour-sergeant. There were two men that loved her, and one that she loved, and you’ll smile when you look at this poor thing huddled before the fire and hear me say that it was for my good looks that she loved me.

“Well, though I had her heart, her father was set upon her marrying Barclay. I was a harum-scarum, reckless lad, and he had had an education and was already marked for the sword-belt. But the girl held true to me, and it seemed that I would have had her when the Mutiny broke out, and all hell was loose in the country.