Lestrade laughed indulgently. “You have, no doubt, already formed your conclusions from the newspapers,” he said. “The case is as plain as a pikestaff, and the more one goes into it the plainer it becomes. Still, of course, one can’t refuse a lady, and such a very positive one, too. She had heard of you, and would have your opinion, though I repeatedly told her that there was nothing which you could do which I had not already done. Why, bless my soul! here is her carriage at the door.”

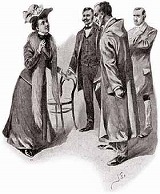

He had hardly spoken before there rushed into the room one of the most lovely young women that I have ever seen in my life. Her violet eyes shining, her lips parted, a pink flush upon her cheeks, all thought of her natural reserve lost in her overpowering excitement and concern.

“Oh, Mr. Sherlock Holmes!” she cried, glancing from one to the other of us, and finally, with a woman’s quick intuition, fastening upon my companion, “I am so glad that you have come. I have driven down to tell you so. I know that James didn’t do it. I know it, and I want you to start upon your work knowing it, too. Never let yourself doubt upon that point. We have known each other since we were little children, and I know his faults as no one else does; but he is too tender-hearted to hurt a fly. Such a charge is absurd to anyone who really knows him.”

“I hope we may clear him, Miss Turner,” said Sherlock Holmes. “You may rely upon my doing all that I can.”

“But you have read the evidence. You have formed some conclusion? Do you not see some loophole, some flaw? Do you not yourself think that he is innocent?”

“I think that it is very probable.”

“There, now!” she cried, throwing back her head and looking defiantly at Lestrade. “You hear! He gives me hopes.”

Lestrade shrugged his shoulders. “I am afraid that my colleague has been a little quick in forming his conclusions,” he said.

“But he is right. Oh! I know that he is right. James never did it. And about his quarrel with his father, I am sure that the reason why he would not speak about it to the coroner was because I was concerned in it.”

“In what way?” asked Holmes.

“It is no time for me to hide anything. James and his father had many disagreements about me. Mr. McCarthy was very anxious that there should be a marriage between us. James and I have always loved each other as brother and sister; but of course he is young and has seen very little of life yet, and- and-well, he naturally did not wish to do anything like that yet. So there were quarrels, and this, I am sure, was one of them.”

“And your father?” asked Holmes. “Was he in favour of such a union?”

“No, he was averse to it also. No one but Mr. McCarthy was in favour of it.” A quick blush passed over her fresh young face as Holmes shot one of his keen, questioning glances at her.

“Thank you for this information,” said he. “May I see your father if I call to-morrow?”

“I am afraid the doctor won’t allow it.”

“The doctor?”

“Yes, have you not heard? Poor father has never been strong for years back, but this has broken him down completely. He has taken to his bed, and Dr. Willows says that he is a wreck and that his nervous system is shattered. Mr. McCarthy was the only man alive who had known dad in the old days in Victoria.”

“Ha! In Victoria! That is important.”

“Yes, at the mines.”

“Quite so; at the gold-mines, where, as I understand, Mr. Turner made his money.”

“Yes, certainly.”

“Thank you, Miss Turner. You have been of material assistance to me.”