“He often had a wild way of talking, so that I thought little of what he said. He followed me to my room, however, that night with a very grave face.

“ ‘Look here, dad,’ said he with his eyes cast down, ‘can you let me have £200?’

“ ‘No, I cannot!’ I answered sharply. ‘I have been far too generous with you in money matters.’

“ ‘You have been very kind,’ said he, ‘but I must have this money, or else I can never show my face inside the club again.’

“ ‘And a very good thing, too!’ I cried.

“ ‘Yes, but you would not have me leave it a dishonoured man,’ said he. ‘I could not bear the disgrace. I must raise the money in some way, and if you will not let me have it, then I must try other means.’

“I was very angry, for this was the third demand during the month. ‘You shall not have a farthing from me,’ I cried, on which he bowed and left the room without another word.

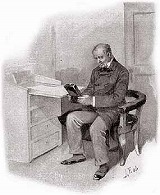

“When he was gone I unlocked my bureau, made sure that my treasure was safe, and locked it again. Then I started to go round the house to see that all was secure -a duty which I usually leave to Mary but which I thought it well to perform myself that night. As I came down the stairs I saw Mary herself at the side window of the hall, which she closed and fastened as I approached.

“ ‘Tell me, dad,’ said she, looking, I thought, a little disturbed, ‘did you give Lucy, the maid, leave to go out to-night?’

“ ‘Certainly not.’

“ ‘She came in just now by the back door. I have no doubt that she has only been to the side gate to see someone, but I think that it is hardly safe and should be stopped.’

“ ‘You must speak to her in the morning, or I will if you prefer it. Are you sure that everything is fastened?’

“ ‘Quite sure, dad.’

“ ‘Then, good-night.’ I kissed her and went up to my bedroom again, where I was soon asleep.

“I am endeavouring to tell you everything, Mr. Holmes, which may have any bearing upon the case, but I beg that you will question me upon any point which I do not make clear.”

“On the contrary, your statement is singularly lucid.”

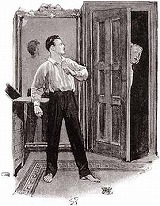

“I come to a part of my story now in which I should wish to be particularly so. I am not a very heavy sleeper, and the anxiety in my mind tended, no doubt, to make me even less so than usual. About two in the morning, then, I was awakened by some sound in the house. It had ceased ere I was wide awake, but it had left an impression behind it as though a window had gently closed somewhere. I lay listening with all my ears. Suddenly, to my horror, there was a distinct sound of footsteps moving softly in the next room. I slipped out of bed, all palpitating with fear, and peeped round the corner of my dressing-room door.

“ ‘Arthur!’ I screamed, ‘you villain! you thief! How dare you touch that coronet?’

“The gas was half up, as I had left it, and my unhappy boy, dressed only in his shirt and trousers, was standing beside the light, holding the coronet in his hands. He appeared to be wrenching at it, or bending it with all his strength. At my cry he dropped it from his grasp and turned as pale as death. I snatched it up and examined it. One of the gold corners, with three of the beryls in it, was missing.

“ ‘You blackguard!’ I shouted, beside myself with rage. ‘You have destroyed it! You have dishonoured me forever! Where are the jewels which you have stolen?’

“ ‘Stolen!’ he cried.

“ ‘Yes, thief!’ I roared, shaking him by the shoulder.

“ ‘There are none missing. There cannot be any missing,’ said he.